Share this @internewscast.com

I keep hearing the same sentence repeating in my head.

“My vision is that every American is wearing a wearable within four years.”

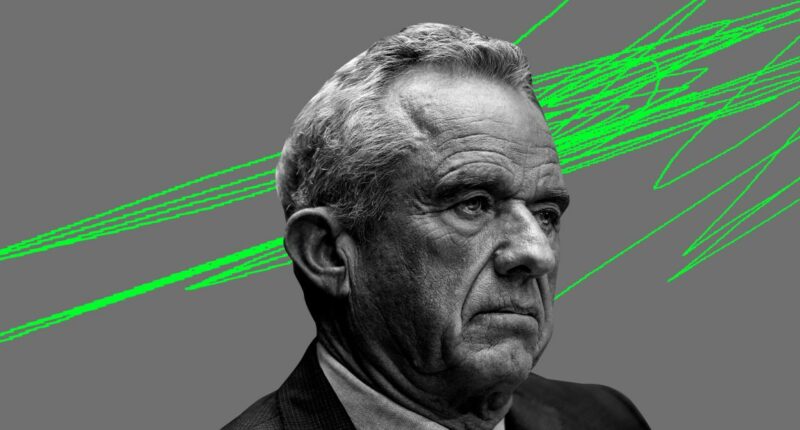

At a congressional hearing in late June, RFK Jr., the current secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services, highlighted the significance of wearables for the MAHA — Make America Healthy Again — initiative. According to Kennedy, wearables empower Americans to “take control” or “take responsibility” for their health by offering insights on how lifestyle choices impact their metrics. During the hearing, he also shared anecdotes of friends who had lost weight and reversed their diabetes diagnoses using continuous glucose monitors (CGMs).

As a wearables expert, I don’t oppose these devices. However, Kennedy’s vision of a “wearable for every American” seems to suggest that everyone will benefit from such technology, which isn’t entirely accurate.

In 2014, I began using a Fitbit to lose weight after unexpectedly gaining 40 pounds in six months. I started exercising, dieting, and closely monitoring my steps—reaching 10,000 to 15,000 daily, regardless of the weather. I consumed as few as 800 calories while maintaining 15,000 daily steps—equivalent to about 7.5 miles for me. Although Kennedy claims that this data can improve health, my experience was different. Despite having plenty of data, I couldn’t figure out how to “take control” of my health, and I continued to gain weight.

That period was emotional, filled with tears. My mom, deeply affected by my sudden avoidance of carbohydrates, couldn’t understand. Even though I improved my running and measured every food portion meticulously, each visit to the doctor was frustrating. I’d share my Fitbit data, desperate for acknowledgment, but they didn’t know how to use it. Communication was a barrier too, and their suggestions ranged from going vegan to trying harder due to my slow metabolism. By 2016, after gaining another 20 pounds, I was diagnosed with polycystic ovary syndrome—a condition contributing to weight gain and insulin resistance.

Wearables did clue me in on an underlying issue, but the journey to understanding was challenging. Despite these hurdles, the technology did enhance some health aspects. I’ve become more active: I progressed from struggling with a single mile to successfully completing two half-marathons, several 10Ks, and numerous 5Ks. My sleep pattern is more consistent, and my resting heart rate improved—from 75 bpm during sleep to about 55 bpm. My cholesterol decreased, and while my weight fluctuated, I’ve managed to maintain a 25-pound loss from the 60-pound gain due to PCOS, and I’ve gained muscle.

What I haven’t shared quite as publicly is that these improvements came at a heavy cost to my mental health.

The initial three years with wearables strained my relationship with food. Although I faithfully tracked my data, I saw little progress, with limited guidance on applying data insights healthily. I fixated on anything that might help me achieve my goal, leading to disordered eating. Many wearable apps prominently feature food logging, prompting me to meticulously weigh and record all my intake for years. If I exceeded my calorie budget by even 15 calories, I’d go for a run to burn 50 calories and get back on track. Social events became a challenge due to uncertain calorie logs when eating out. If my progress stagnated, I’d punish myself by skipping meals. Per my therapist, these behaviors suggested mild orthorexia nervosa and anorexia.

I also started developing anxiety about my running performance. If I wasn’t improving my VO2 Max or mile times, I was failing. It didn’t matter that I’d gone from running 16-minute miles to recording a personal best of 8 minutes, 45 seconds. Any time I became injured, my numbers would go down, and I’d feel like a complete failure. When my father died, I was stuck in a funeral home in the Korean countryside, pacing around in circles so that I wouldn’t lose my step streak. Ironically, in a bid to please my wearable overlords, I’ve ended up injuring myself several times through overexercise in the last decade.

I’m okay now, thanks to a lot of work in therapy and the help of my loved ones. But healing isn’t a one-and-done kind of thing. Ninety-five percent of the time, I use wearables in a much more reasonable way. I take intentional breaks the other five percent of the time, whenever old habits rear their ugly head.

Mine isn’t a unique experience. Several studies and reports have found that wearables can increase health anxiety. Anecdotally, when a friend or acquaintance gets a new wearable, I usually get one of two types of messages. The first is an obsessive recounting of their data and all the ways they monitor food intake. The other is a flurry of worried texts asking if their low HRV, heart rate, or some other metric is a sign that they’re going to die. Most of these messages come from people who have had a recent health scare, and I usually spend the next hour teaching them how to interpret their baseline data in less absolute terms. And therein lies the rub. These devices overloaded the people in my life with too much information but not enough context. How can anyone effectively “take control of their health” if they’re struggling to understand it?

There’s never been, nor will there ever be, a one-size-fits-all solution.

There’s never been, nor will there ever be, a one-size-fits-all solution. That’s why I’m skeptical that Kennedy’s vision is even feasible. Doctors don’t always know how to interpret wearable data. Not only that, it’d be a massive undertaking to give every American a wearable. There are dozens, if not hundreds, of products on the market, and everyone’s health needs are unique. Would the government subsidize the cost? Where do health insurance companies, FSAs, and HSAs fit into this picture? So far, all we’ve heard from Kennedy is that the HHS plans to “launch one of the biggest advertising campaigns in HHS history” to promote wearable use.

But even if Kennedy were to solve this logistical nightmare, I take issue with framing wearables as a necessary component in anyone’s health journey. You risk creating scenarios where insurance companies use wearables as a means of lowering or raising premiums, similar to how certain car insurance providers use telematics devices to monitor their customers’ driving in exchange for discounts. It sounds good in theory, but it also opens the door to discrimination. Some, but not all, illnesses can be treated or prevented through lifestyle changes.

Not everyone will experience the darker side of this tech like I have. But I know that many have, and many more will. Some, like me, will eventually find a healthy balance. For others, the healthiest thing they could do is to avoid wearables.