Share this @internewscast.com

As the NFL season kicks off, numerous players will don the latest F7 Pro helmet, renowned for its subtle yet significant differences – some even suggest it could be the safest football helmet available. This development holds importance for a sport famously associated with concussions over the past two decades, as much as it is with touchdown celebrations. Schutt Sports, the manufacturers of the F7 Pro, proudly state that 35% of NFL athletes have switched to using this helmet.

In football, tradition plays a vital role, especially with such gear. A prime example is the Pittsburgh Steelers’ quarterback, Aaron Rodgers, a long-time user of Schutt’s products. The model he previously wore, the Schutt Air XP Pro Q11 LTD, has now been banned by the NFL, failing to meet its escalating safety standards. He has found it difficult to adjust to its successor, the Schutt Air XP Pro VTD II, describing it as having a “spaceship” appearance. (The F7 Pro didn’t win his approval either.)

“There’s a limit to how big a helmet can be before players won’t adopt it because you’ll feel like you look more like a bobble head.”

Jason Neubauer, the Chief Innovation Officer for Certor Sports, which owns Schutt and VICIS brands, notes that unlike most other sports, in football, a fresh design isn’t typically as highly sought after.

“In over 25 years of designing sporting goods, in nearly every other category, there’s a demand for new products,” Neubauer states. “Yet in the football helmet realm, it’s reversed. Introducing a brand-new design can take two or three years to gain popularity.”

The Schutt F7 Pro’s release coincides with a milestone in the NFL’s efforts to curb concussions and injuries. The league observed a 17% decrease in concussion rates during the 2024 season across both practices and games, marking the lowest figures since the league began recording in 2015, following prolonged denial of the issue and reluctance to reimburse affected players.

This decline in concussions isn’t attributed solely to advanced helmet technology. Last year, the NFL altered the kickoff rules, a play commonly associated with concussions, and required specific positions to wear Guardian caps over helmets during practice. (Notably, some top new helmets, including two from Schutt, don’t need caps in practice.) Enhanced education, upgraded concussion protocols, and improved injury monitoring contribute to this success. Helmets are just one element in the broader effort to mitigate concussions.

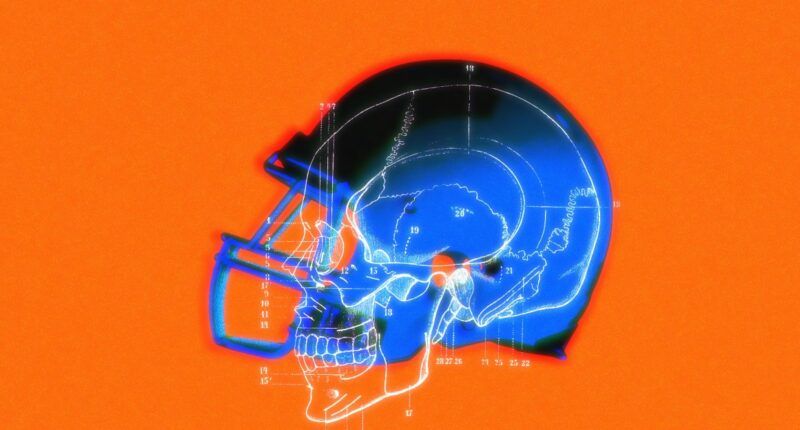

But it’s the most visible one. A football helmet is more than a protective layer over the player’s head. It has come to symbolize the game itself. Old Monday night football promos show animations of two helmets emblazoned with the logos of the two opposing teams, crashing into each other, head on, nary a ball in sight.

“Every other sport, it’s something part of the gameplay. It’s the bat or the mitt or the ball in baseball. It’s the ball in basketball. It’s the stick and puck in hockey. It’s never the safety device [that’s] the symbol of the game the way it is in American football,” Noah Cohan, a professor of American studies at Washington University who is working on a history of the helmet, points out.

What this all means is that the designers of the new Schutt and other models cannot set aside aesthetic considerations and think only of improved impact performance. “There’s a limit to how big a helmet can be before players won’t adopt it because you’ll feel like you look more like a bobble head,” Neubauer says. Or a spaceship, to put it into Rodgers’ parlance. The most straightforward way to make the helmet more protective is to make it bigger. The more a helmet can deform, the more energy it can keep away from an athlete’s head and an unstable brain sloshing around inside a skull. “But if no one accepts it as a product they were willing to use, it’s just a spot on the poster or a pretty prototype at that point.”

Neubauer explains that they didn’t want to make any major changes to the exterior look of the helmet — which has probably helped with the speed of adoption since the look and feel is probably familiar to many players — so that left them with the interior to play with in order to improve impact performance. There’s the AiR-Lock feature, which allows players to better customize the helmet’s fit on their heads by simply pressing a button at the back to pump air in. To that end, they created DNA Core, a printed 3D lattice structure for inside the shell that is designed around polyps that are made to first resist and then buckle. “The concept there is that you slow down the impact a little bit before you actually start to compress the pad,” Neubauer says, describing a process of the interior material thinning out all over upon impact. “The goal of that micro lattice is to obviously crush and bend and absorb the impact to the fullest extent.”

“The goal of that micro lattice is to obviously crush and bend and absorb the impact to the fullest extent.”

Other helmet brands also use 3D printing and customization in their design. The Riddell Axiom3D, which also tops on the NFL rating list, has it right there in the name. “While 3D printing has been used in other helmets before — including by our sister brand VICIS, which integrated 3D-printed custom-fit pads into a model in 2020 — this marks the first time Certor Sports has 3D-printed the entire impact structure of a helmet,” Neubauer says. Riddell, the brand that brought the plastic football helmet to the market back in the 1930s, remains at the top of the NFL’s ratings and usage according to back-of-the-napkin math I did based on Helmet Stalker’s Instagram account. But this model, unlike the Schutt F7 Pro, has been on the market for over a year. So if Neubauer’s logic about adoption rates hitting their stride in the second or third year after introduction holds, then the F7 Pro could become dominant in the space. Or a corporate rival could come along with another, even better helmet that overtakes its predecessors.

This is the way that things have been trending since at least 2011, when the Virginia Tech testing lab began issuing its summation of tests and assessment of risk (STAR). “At the time, we only identified one five-star helmet,” says Steve Rowson, the lab’s current director. “We identified a handful of four stars but most notably, one of the most popular helmets at the time was only rated as one star. There’s big implications on differences in risk between those two categories.”

“That had a dramatic effect on the industry,” Rowson says of their ratings.

The helmet industry needed outsight oversight because, left to their own devices, they made some highly dubious claims about the efficacy of their products. In No Games for Boys to Play: The History of Youth Football and the Origins of a Public Health Crisis, Kathleen Bachynski writes, “In 1954, Rawlings asserted that its helmets could dissipate ‘over 75% of sharp sudden and sudden impact,’ providing ‘the Safest, Surest Head Protection ever developed for football.’”

Things have certainly improved since the 1950s but even more so since Virginia Tech, and then the NFL, started testing the helmets rigorously. Rowson is encouraged by the improvements he’s seen in the design and manufacture of helmets. “The helmet manufacturers should really be applauded for the progress they [have] made over the past 15 years. The best helmet back when we first released our helmet ratings in 2011 would be the worst helmet today by a wide margin,” he says. If you click your way through Virginia Tech’s varsity rating guides, neither the Riddell nor Schutt models are at the very top of the heap. (Rowson said they hadn’t yet tested these models but they plan to in the near future.) But the top 11 have all been evaluated at five stars.

But the question that remains is: how much safer can they get?

“I think what’s left on the table, at this point, is how can they further advance materials that are going inside the helmets?” Rowson notes. “As more advanced materials come out, perhaps helmet performance is going to be able to inch forward.”

But the caveat on Schutt’s website that “no helmet can prevent head, brain, or neck injuries, including paralysis or death, a player might receive while participating in football” is more than simply a standard cover-your-ass kind of statement to stave off lawsuits, which helmet manufacturers found themselves the target of in the early days of the equipment. It’s an acknowledgement of the truth. A helmet, on its own, can’t prevent these serious outcomes.

“The helmet is the last line of defense,” Rowson says about the contact collision sport where risk can only be managed, never eliminated.

0 Comments