Share this @internewscast.com

As the chill of January takes hold, many British households might find themselves questioning the cozy warmth of their wood-burning stoves. This reflection comes as environmental groups observe their yearly “clean air night,” an initiative designed to spotlight the health risks associated with wood burning.

This initiative is spearheaded by Global Action Plan, a charity committed to educating the public about the dangers of wood smoke. According to the group, the smoke emits harmful particles that can penetrate deeply into the lungs.

Research highlights the presence of tiny particles, known as PM2.5, in wood smoke. These particles are small enough to enter the bloodstream, potentially causing irritation and inflammation that may lead to serious health issues such as heart disease, lung disease, strokes, cancer, and even dementia.

The impact of PM2.5 is not confined to indoor spaces; these particles can also affect outdoor air quality if they accumulate to high levels.

In a 2022 report, Sir Chris Whitty, then the chief medical officer, revealed that even the latest wood burners emit 450 times more toxic pollution than gas central heating systems.

Furthermore, a study released by Action For Clean Air in October suggested that eliminating non-essential wood burning could save the NHS over £54 million each year and potentially avert thousands of deaths.

The noose is tightening for wood burners in London and other British cities such as Bristol, Bath, Nottingham, Coventry, Oxford and Reading that now have Smoke Control Areas where you can be fined for burning wood in your sitting room.

But the wood burner industry is hitting back with claims that this popular middle-class heating method is being unfairly pilloried.

They insist the health risks are exaggerated and claim that the ‘nanny state’ is trying to take away a source of comfort.

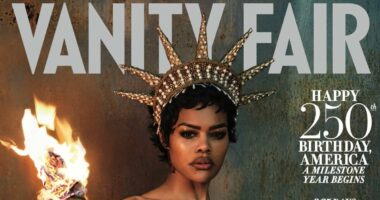

Louise Atkinson (pictured) asks: ‘Are you risking your health and that of your neighbours every time you light your wood burner?’

Louise bought a device that monitors PM2.5 emissions in the air to investigate the issue of harmful emissions in the home

‘Frying eggs is more interesting as merely heating oil in the frying pan takes the PM2.5 levels to 80 and 109.6 when the eggs are cooked’, Louise Atkinson writes

Some argue that wood is a green and renewable source of energy, and that the anti-burner campaign is probably backed by big energy companies keen to sell electricity and gas instead.

So, what is the truth? Are you risking your health and that of your neighbours every time you light your wood burner? Is it time to brick up your fireplace and gather the family around a radiator instead?

In search of an unbiased opinion, I talk to respiratory immunologist Dr Ross Walton. ‘Wood smoke can cause irritation and damage,’ he tells me, but adds it is important to understand that prolonged exposure causes the most damage.

He points out that in developing countries which cook on solid wood fires, incidence of lung conditions such as COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) is significantly higher – particularly among women and children who spend more time near the fires.

He says certain populations – the elderly and the very young – are at greatest risk of damage from PM2.5 inhalation, but otherwise healthy people might also be vulnerable, for example, when recovering from a cold.

The debate is muddied by the fact that PM2.5 levels outside the home are massively raised by vehicle exhaust fumes, and inside, ordinary household activities such as cooking, cleaning and burning scented candles can raise PM2.5 levels far higher than a wood burner might.

On the Instagram page of his stove company, Firefly London owner Angus Muir shows a futuristic looking wood burner fully stoked, with a hand-held sensor recording a PM2.5 reading of 9.7 micrograms per cubic meter – firmly in the ‘clean air’ category (according to the World Health Organisation) – and the same sensor over a pot of bubbling bolognese sauce on a gas hob reading a ‘hazardous’ PM2.5 of 971.5 micrograms per cubic meter.

‘How do you rationalise the harm to health caused by modern wood-burning stoves when the air quality in every domestic kitchen in the country is consistently hazardous?’ he asks.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), a reading below five denotes perfectly clean air and anything between five and 15 is acceptable

‘How can you be sure the exposure to PM2.5, which cause health problems, is generated by wood-burning stoves and not from the kitchen where we spend the vast majority of our time?’

To check this theory, I buy a hand-held device that monitors PM2.5 emissions in the air (it cost £150) and set up a series of tests to measure PM2.5 levels in my home. The results are eye-opening.

I am reassured to see the base level in my converted barn in the Cotswolds sits at seven micrograms per cubic metre.

According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), a reading below five denotes perfectly clean air and anything between five and 15 is acceptable.

Fifteen to 25 is considered ‘poor’ and anything over 25 ‘harmful’. When the numbers nudge above 100, you enter ‘hazardous’ territory.

Boiling a pan of water on the gas hob takes the level up to 26.6 with a peak at 31.7. Frying eggs is more interesting as merely heating oil in the frying pan takes the PM2.5 levels to 80 and 109.6 when the eggs are cooked.

Worryingly, the level continues to rise after I turn off the heat, peaking at 249.7 (‘hazardous’) and staying high for 15 minutes before returning to original levels.

Now time to toast a bit of bread. The monitor settles on 30.9, but as soon as the edges start to burn, the numbers fly up to 608.1, briefly hitting the max at 999.9 before coming down (slightly) to 970.4.

In 2022, a report by Sir Chris Whitty, then chief medical officer, found that even the most modern wood burners produce 450 times more toxic air pollution than gas central heating (File image)

Even after I turn on the extractor fan and open the door to let the smoke out, the PM2.5 levels stay worryingly high for 45 minutes.

‘You’re likely to get a much higher spike of PM2.5 when you burn food than you would from a wood burner,’ says Dr Walton, ‘but those brief spikes are not dangerous. It’s the extended exposure that might create a cumulative load.’

So a quick blast of high PM2.5 might irritate airways and eyes, worsen asthma and potentially raise your blood pressure, but studies show vulnerable people (the very young, the very old, or those with asthma) start to see temporary cardiovascular changes after only one to two hours.

One short burst can cause irritation, repeated exposure causes lasting damage and long-term accumulation raises cancer risk.

But what if you spend most of your day in the kitchen, as I do?

Armed with my testing device, I try a spot of vacuuming. I was warned that this can kick up dust and I anticipate a big spike of PM2.5 because of the grime brought in regularly by our large dog.

But even enthusiastic vacuuming only lifts the reading from 4.7 to 5.5. Once I had put the vacuum away, the level rises a little further to 10.3 (presumably because of dust now in the air), staying there for 15 minutes before returning to the room’s base level.

I’m not optimistic about generating a high reading by flicking a duster around, but ours is a very old house so dust accumulates quickly. Within a few minutes the reader jumps to 39.3, which the monitor declares to be ‘unhealthy for sensitive groups’.

I move to the downstairs loo, throwing a bit of bleach around (no change on the PM2.5 monitor) and spritzing the air with a natural, aromatherapy air freshener. Just one blast takes the reading up to 90.5.

I’m clearly sensitive to housework and decide to stop for the sake of my health.

Curling up on the sofa with a book, I light a collection of scented candles. Surely these will be innocuous enough?

I keep a close eye on the monitor, which rises to 8.4 then stabilises at a perfectly reasonable 5.5. But when I stand close to the candles, the monitor goes completely crazy, peaking at 594.22.

I blow them out, thinking I had removed the problem but, to my horror, the smoke drifting up sends the monitor into orbit and a 999.9 reading.

Although the acrid whiff of snuffed candle dissipates in minutes, the monitor reading stays high. After 15 minutes, levels are still at 102 (unhealthy) and it takes a full hour for the reading to drop to 12 (good).

Could an evening of scented candles be just as unhealthy as one in front of a wood burner?

According to the Stove Industry Association (SIA), 1.9 million households in the UK use wood fuel indoors and their independent testing has shown that when used properly, modern wood burners (those manufactured after 2017) can reduce PM2.5 dramatically compared with open fires and with older stoves by up to 80-90 per cent.

So I fully expected the reading from our open fire to be appalling. We only light it occasionally but it is a much-loved part of our home.

I brace myself for a ‘hazardous’ reading as the flames crackle but, although the monitor does peak at 58.8, it quickly drops to 36.8 and the levels continue to fall over the next hour, settling at a perfectly reasonable 8.9 for most of the evening.

PM2.5 levels outside the home are massively raised by vehicle exhaust fumes

I can only assume that the emissions, like much of the heat, were going straight up the chimney.

The real test will be on a wood burner. Erica Malkin from the SIA informs me that emissions are likely to be higher in a home with an old burner (newer ‘eco-design’ models have been reconfigured for better efficiency) and an unswept chimney, particularly if you are in the habit of throwing any old wood and rubbish on to the fire.

Angus Muir sends me a fresh set of PM2.5 readings from the ultra-modern wood burner he has at home.

Although he gets a blast of PM2.5 up to 30.6 just after lighting the stove while the door is open, this falls to 15.3 when the door is closed and settles on 11.3, which is still in the ‘clean air’ category.

I ask two neighbours if I can measure the emissions from their wood burners. The first tells me her burner was installed in 2012 and she can’t remember when the chimney was swept so I’m anticipating higher readings.

Sure enough, the monitor leaps up to 301 as she lights the fire, hovers between 60 and 70 for half an hour before eventually settling at 32.6 (levels that WHO would consider ‘harmful’).

But these are not laboratory conditions, and I later learn that she had been furiously cleaning the house in anticipation of my visit (which will have raised PM2.5 levels in the air) and had lit scented candles in my honour. This would certainly have skewed the results.

Another neighbour has a brand new burner and swept chimney. After lighting the fire and closing the door, my monitor reads a reassuring 19.2 but ribbons of dark smoke start escaping. The alarm on my monitor sounds as the numbers rattle up to the 100s.

My friend tells me this has never happened before, but it’s usually her husband who lights the fire. She fiddles with the vents and we throw open windows.

The fire settles, but residual smoke takes a long time to dissipate and the monitor is reading 46.3 90 minutes later, eventually resting at 37.

One short burst of PM2.5 emissions can cause irritation, while repeated exposure causes lasting damage and long-term accumulation raises cancer risk

It is clear that emission levels fluctuate in any home and there are many factors that contribute to your PM2.5 exposure.

So what’s the best advice if you really do love your wood burner?

Dr Walton says: ‘The majority of risks for an otherwise healthy population can logically be mitigated by using the wood burner properly, and be considerate of who is in the house and how it might affect them.’

It’s also probably a good idea to cook with your extractor fan on and to keep a very close eye on the toast.