Share this @internewscast.com

Initially, Weiss didn’t think it was significant “because whales do weird things,” he remarked. However, further drone footage showed similar behaviors.

“I zoom in, and sure enough, there’s clear as day this piece of kelp that they’re using to rub on each other.”

Over the course of just two weeks in 2024, Weiss and his team documented 30 examples of these curious interactions.

It turned out that the southern resident orcas — a unique group of killer whales — were pulling strands of bull kelp from the seafloor to roll between their bodies, a behavior scientists termed “allokelping.”

This discovery is the first recorded instance of cetaceans — marine mammals like whales, dolphins, and porpoises — using an object as a tool for grooming purposes.

Across the animal kingdom, using tools is rare, according to behavioural ecologists. But when it does happen, it’s often for finding food or attracting mates.

“This is a quite different way of using an object,” said Weiss, the study’s lead author and research director of the Centre for Whale Research in Washington state.

There are two possible reasons behind the allokelping behaviour, Weiss and his team hypothesise.

The other hypothesis, Weiss explained, is that allokelping is a way to strengthen social bonds, as the whale pairs seen exhibiting this behaviour were usually close relatives or similar in age.

“These guys are incredibly socially bonded,” said Deborah Giles, an orca scientist at the SeaDoc Society who was not involved with the research. This behaviour is fascinating but not entirely surprising, she added.

Cetaceans also have sensitive skin, explained Janet Mann, a behavioural ecologist at Georgetown University who has studied marine mammals for 37 years. Orcas are known to rub on other objects such as smooth-pebble beaches in Canada, or on algal mats. But it’s unusual to see two individual killer whales using a tool to seemingly exfoliate each other, she said.

“What (the study) shows is that we know very little about cetacean behaviour in the wild,” Mann said.

Allokelping likely wouldn’t have been discovered without advances in drone and camera technology, which have opened up “a whole new world” for scientists to better understand cetaceans’ complex lifestyles, Mann said.

Historically, whales are observed from shore or from boats, offering a limited perspective of what’s happening in the water. But drones offer a bird’s-eye view of what marine animals are doing just below the surface. It’s likely this population has been allokelping for a while, she said â only now we can see it.

Orca scientists with drone footage are probably going to be on the lookout for this sort of behaviour now, Giles said.

Whether these examples constitute “using tools” is a topic of debate in the scientific community, but regardless, they are all behaviours related to foraging for food. What makes allokelping unique is its potential benefits for skin health and relationships â in other words, it appears to be a cultural practice.

“This idea of allogrooming (with tools) is largely limited to primates, which is what makes it remarkable,” said Philippa Brakes, a behavioural ecologist with the nonprofit Whale and Dolphin Conservation who was not involved with the research.

“This kind of feels like a moment in time for cetaceans, because it does prove that you don’t necessarily need a thumb to be able to manipulate a tool.”

Brakes, who studies social learning and culture in cetaceans, added that this new research “tells us quite a lot about how important culture is for these species.”

Each population â in this case, southern resident orcas â has a distinct dialect for communication, specific foraging strategies and now a unique type of tool use.

In a rapidly changing environment, Brakes said, “culture provides a phenomenal way for animals to be able to adapt,” as it has for humans.

“It’s more reason to ensure that we protect their habitat as well as their behavior,” she noted.

A ‘completely novel’ find

Indeed, southern resident killer whales are critically endangered and federally protected both in the United States and Canada, with a total population of just 74 whales.

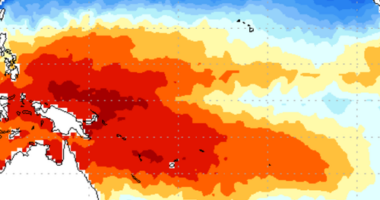

And as bull kelp is in decline due to human activities that disrupt the seabed and more frequent heat waves caused by climate change, the overall ecosystem is degrading.

“This study makes me wonder if one of the reasons the Southern Residents continue to visit the Salish Sea periodically even during times of low salmon abundance is to engage in allokelping,” Shields wrote in an email to CNN.

The research is now leading to new areas of study.

“This cetacean data point is a really important one because it’s completely novel,” said Dora Biro, an animal cognition researcher at the University of Rochester who was not involved with the study.

Biro, who has mostly studied tool use in wild chimpanzees, added that examples of terrestrial tool use are much more widespread than in aquatic environments. She is now working on a grant proposal with Weiss’ team to better understand the purpose of the behavior.

But for Brakes, there doesn’t necessarily need to be a purpose: “The objective may just be social bonding, and that would still make it a tool.”