Share this @internewscast.com

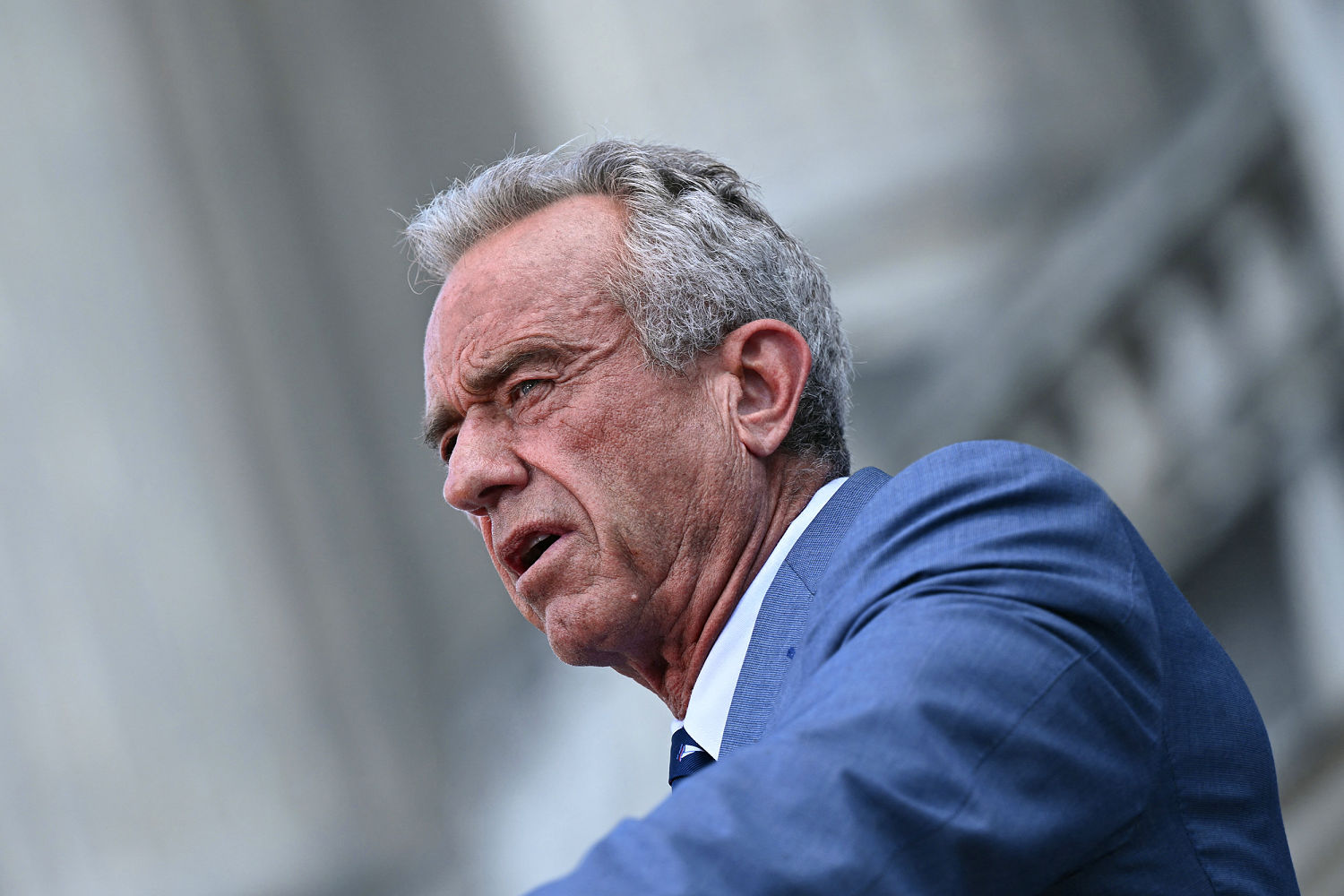

When Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. dismissed all members of a key vaccine panel earlier this summer, he justified the move by stating that the committee had “persistent conflicts of interest.”

However, a new study, published Monday in the Journal of the American Medical Association, reveals that for almost the past ten years, the two major vaccine advisory committees have had historically low levels of conflicts of interest.

Kennedy has consistently argued that the members of the vaccine advisory panels at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Food and Drug Administration maintain strong ties with the pharmaceutical industry. During his initial confirmation hearing in January, Kennedy claimed that a staggering 97% of CDC advisers had conflicts of interest.

“When he cited these large statistics like 97%, I thought, ‘Wow, that’s really significant,’” remarked Genevieve Kanter, the study’s lead author and an associate professor of public policy at the University of Southern California Sol Price School of Public Policy. “However, when I reviewed the vaccine data, I didn’t observe such high figures.”

The study investigated the prevalence of conflicts of interest over the past twenty years for members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) and the FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC).

During that time period, the vaccine panels each met about four times a year, with the most frequent meetings happening from 2016 through 2024.

The study found that since 2016, only 6.2% of ACIP members and 1.9% of VRBPAC members have reported a conflict of interest at any given meeting.

Moreover, the type of conflict often seen as most concerning — financial ties to vaccine manufacturers — had been nearly eradicated within both committees.

Of those with reported conflicts of interest, less than 1% involved personal income from vaccine companies, such as consulting fees, royalties, stocks or ownership, the study found.

Kanter said that in the early 2000s, conflicts of interest on the committees were much higher — peaking at 43% for ACIP in 2000 and 27% for VRBPAC in 2007.

Back then, it was generally the accepted norm for advisory committee members to have conflicts of interest, she added.

But starting around 2007 and 2012, members of the FDA’s VRBPAC started to undergo a more stringent vetting process, including requirements to disclose conflicts of interest and recuse themselves from voting on vaccines for which conflicts exist, Kanter said. It’s less clear when ACIP started to push for a more rigorous vetting process, she said.

For ACIP, reported conflicts fell to 5% by 2024. For VRBPAC, reported conflicts have stayed below 4% since 2010, including 10 years where there were no reported conflicts at all.

“They’re relatively low,” Kanter said. “Although there are certainly some who advocate for zero conflict or financial interests.”

It’s difficult to create an advisory panel of experts with no conflicts of interests, she added.

The panels are typically made up of top experts in the fields of infectious diseases, pediatrics, immunology and public health. Vaccine makers often reach out to these experts to oversee their clinical trials or to play an advisory role when developing a new product.

“It’s a balancing act,” Kanter said. “You do want people who have done the clinical research on safety and efficacy.” She added that her previous research has shown that people who have financial ties to the competitor of any given product being discussed often don’t vote any differently than people who have no financial ties.

In a statement, Andrew Nixon, a spokesperson for the Department of Health and Human Services, said: “Secretary Kennedy is committed to eliminating both real and perceived conflicts to strengthen confidence in public health decisions.”

Dorit Reiss, a vaccine policy expert at the University of California, San Francisco, said it’s important for advisory panels to maintain low conflicts of interest because it helps prevent “skewed decision-making.”

After Kennedy fired all 17 members of ACIP, he replaced them with eight new appointees, including several well-known vaccine critics. (One person dropped out before the committee’s first meeting, leaving the group with seven.)

“Anti-vaccine activists define conflicts of interests differently than the rest of us,” Reiss said. “They believe in a grand conspiracy where pharma controls the media and government, so for them, for example, an NIH grant would be a conflict of interest, or working in a health care organization.”

Several of Kennedy’s new appointees, however, have ties to anti-vaccine groups or have served as expert witnesses in vaccine-related lawsuits, testifying on behalf of the plaintiffs suing vaccine makers.

Lawrence Gostin, a Georgetown University law professor who specializes in public health, said he wasn’t surprised by the new study’s findings, noting that it’s common practice for committee members to recuse themselves from voting if a conflict arises.

Gostin said he believes Kennedy’s rationale for replacing ACIP members was a “mere smoke screen for his real reason,” which was to replace reputable vaccine scientists with anti-vaccine activists.

“Many if not most current members of ACIP have been closely associated with anti-vaccine advocacy groups, including the one previously led by Kennedy,” he said.