Share this @internewscast.com

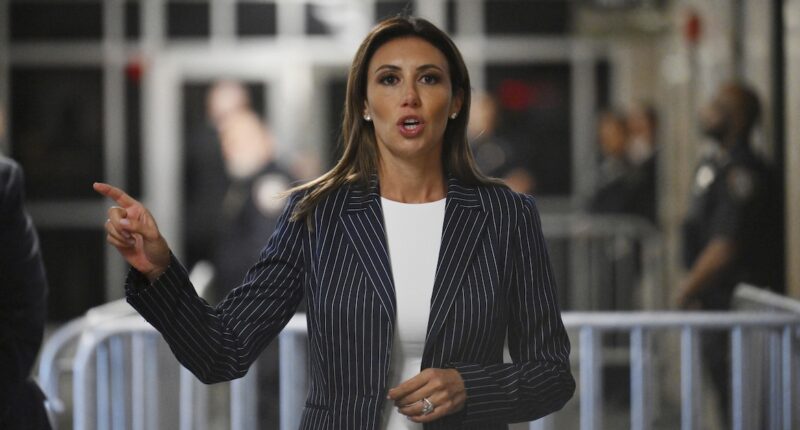

Alina Habba, a lawyer for former President Donald Trump, is seen discussing the case outside the Manhattan criminal court during Trump’s trial in New York, on Monday, April 22, 2024 (photo by Angela Weiss via AP).

In a surprising twist, President Donald Trump’s dedicated lawyer, Alina Habba, has been prohibited from prosecuting two different groups of criminal defendants. These defendants challenged her authority as the alleged Acting U.S. Attorney for the District of New Jersey.

The associated case, which dates back to 2021, involves Julien Giraud Jr. and Julien Giraud III, who are facing several charges regarding a supposed marijuana distribution scheme. At the end of July, the Girauds sought to have the charges dropped, arguing that Habba was not officially appointed.

The ensuing legal kerfuffle called for outside help.

After some initial evaluations by local magistrate and district judges, Chief U.S. District Judge Matthew Brann from the Middle District of Pennsylvania, who was appointed by Barack Obama, was assigned to lead the case.

In one of his first major decisions, Judge Brann stated that the defendants “are not entitled to dismissal” because the requested relief “is not available.” He criticized the defense’s claim that Habba’s appointment status “somehow retroactively taints the indictment, or any aspect of the prosecution that preceded it.”

But that was then.

Following requests for additional motions regarding Habba’s alleged appointment as the top federal prosecutor in New Jersey, the court concluded that she is not authorized to prosecute the Girauds.

In his 77-page memorandum opinion, Brann took the federal government to task for the ways in which he said officials have tried to game the constitutional system establishing the U.S. Senate’s advice and consent role for the people called to lead the U.S. Attorneys office.

“The Executive branch has perpetuated Alina Habba’s appointment to act as the United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey through a novel series of legal and personnel moves,” the opinion begins. “Along the way, it has disagreed with the Judges of the United States District Court for the District of New Jersey and criminal defendants in that District about who should or may lead the office. Faced with the question of whether Ms. Habba is lawfully performing the functions and duties of the office of the United States Attorney for the District of New Jersey, I conclude that she is not.”

In essence, Habba is not an appointed U.S. Attorney because senators telegraphed their intention to shoot down her nomination. So, the DOJ played a game of musical chairs aimed at keeping the 45th and 47th president’s former personal attorney secure in the post.

In short, to keep Habba atop her perch, Trump pulled her nomination to the permanent role and Habba herself resigned before the 120-day statutory period for the acting role expired. Then, Habba’s first assistant was fired and Habba was reinstated in that inferior position under the Federal Vacancies Reform Act – whether or not that onetime first assistant was appointed to serve as U.S. Attorney.

The switcheroo with the fired first assistant, Desiree Leigh Grace, was important because, after Habba’s interim position timed out, Grace was appointed to serve as U.S. Attorney by a judicial order of New Jersey’s federal bench. To hear the DOJ tell it, however, Grace was fired before that order took effect. In the ensuing vacancy and chaos, Habba was the last woman standing – and remains in charge.

But that’s not how it works, Brann said.

Under the law governing the appointment of interim U.S. Attorneys, the 120-day period is spelled out – and so is what happens next. If that time period expires, the district court itself steps in.

“Accepting the Government’s reading would give the Executive a permanent means of thwarting that provision by terminating every section 546(a) appointment on its 119th day,” Brann writes. “Taken to the extreme, the President could use this method to staff the United States Attorney’s office with individuals of his personal choice for an entire term without seeking the Senate’s advice and consent.”

In real terms, the judge’s order dispenses with the practice of presidents repeatedly using interim appointments to circumvent Senate difficulties. The court acknowledges “successive section 546 appointments” have been a “historical practice” of attorneys general but opines that “past practice does not, by itself, create power.”

“Based on the text, context, and statutory history of section 546, the Attorney General is vested with 120 total days to appoint an Interim United States Attorney from the date that she first invokes section 546(a),” the court observes. “Termination of an appointment before the 120-day deadline does not allow another 120-day term.”

The upshot is that Habba’s assumption of the Giraud case is invalid. The court’s ruling also rendered “defective” an indictment she signed off on in a consolidated case involving Cesar Humberto Pina.

“I disqualify Ms. Habba from engaging in the prosecutions of the Girauds and Mr. Pina, and from supervising the same,” Brann concludes. “Any Assistant United States Attorney who prosecutes the Girauds or Mr. Pina under the supervision or authority of Ms. Habba in violation of my Order is similarly subject to disqualification.”