Share this @internewscast.com

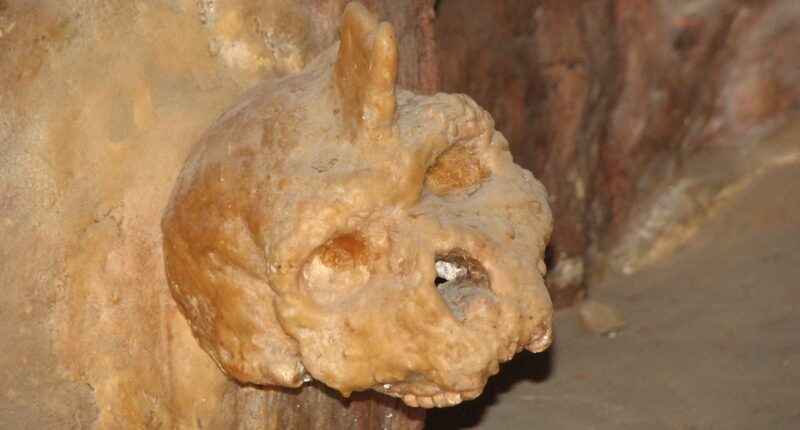

At first glance it looks like nothing of this planet – a creature with a pointed object sticking out of its head, half man, half unicorn.

But scientists are getting closer to unraveling the mystery of the Petralona skull.

The ancient cranium – discovered in Petralona Cave, about 22 miles south–east of Thessaloniki in Greece – is less than 300,000 years old, they say.

It wasn’t a Homo sapiens like us, nor was it a Neanderthal.

‘Determining the age of the nearly complete cranium discovered in the Petralona Cave in Greece is of crucial significance,’ state the collaborative team of researchers from China, France, Greece, and the UK.

‘This fossil has a key position in European human evolution.’

The Petralona skull was uncovered with a distinctive protrusion, which is a stalagmite—a mineral formation that grows upward from the cave floor.

Stalagmites grow slowly as water drips down from the cave ceiling, gaining a millimetre every few years.

The Petralona skull was initially found affixed to the wall within a small cavern in the cave in 1960. A recent study now offers an accurate age estimate for this almost complete cranium.

Determining an accurate age for the nearly complete cranium found in the Petralona Cave in Greece holds ‘crucial significance’ since this fossil occupies a pivotal role in European human evolution.

The Petralona skull was first discovered by local villager Christos Sariannidis in 1960, seemingly just cemented into a cave chamber wall.

Scientists later determined it was fused to the wall by the gradual accumulation of calcite, a common mineral typically found in caves.

Calcite was also present in the large stalagmite extending from its head, which was removed during cleaning before transferring the skull to the Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, where it is currently exhibited.

For this new study, the scientists dated the calcite that grew directly on the ‘nearly complete cranium’, which has the lower jaw missing.

This calcite sample ‘is the only sample able to provide crucial information on the age of the fossil’, the team say in their new paper.

They found that it is at least 277,000 years old, but possibly 295,000 years old, which places it during the later Middle Pleistocene era of Europe.

At the time, Europe was covered in forests and open woodland and the climate was generally more humid and with less pronounced variations in temperature during the seasons.

Previous estimates have spanned about 170,000 to 700,000 years in age – so much less exact.

The Petralona skull was removed and cleaned and is now on display at Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Greece

Pictured, a sample corresponding to the stalagmitic veil, where the cranium was supposed to be attached

This ancient individual would have lived in Europe alongside Neanderthals, the extinct group of archaic humans and our closest ancient human relatives.

However, experts suspect the male individual was part of a different human group known as Homo heidelbergensis, which came before Neanderthals and was more primitive.

European populations of Homo heidelbergensis evolved into Neanderthals, while a separate population of Homo heidelbergensis in Africa evolved into our own species, Homo sapiens.

The Petralona skull was almost certainly male based on the fossil’s size and robustness, which is why it’s also referred to as the ‘Petralona man’.

The skull’s teeth only had moderate wear, so it likely belonged to a young adult, study author Professor Chris Stringer, anthropologist at the Natural History Museum in London, told Live Science.

Even though the Petralona skull was originally found more than 60 years ago it’s been perplexing researchers ever since.

In the early 1980s, the dating of the skull was the subject of a major scientific debate, partly because early results were sometimes difficult to interpret.

Paleoanthropologists variously attributed it to Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis, or ‘archaic Homo sapiens’.

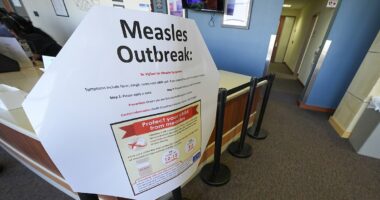

This image shows the elaborate mineral formations inside the Petralona Cave in Greece, which is open to tourists

Fossil evidence suggests species such as Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis lived in Africa and other regions during the period of Group A and Group B. Pictured, the most complete skull of an Homo heidelbergensis ever found

‘This topic has been debated since its discovery more than 60 years ago, highlighting the difficulties in applying physical dating methods to prehistoric samples,’ the team say.

But their new study, published in the Journal of Human Evolution, gives the closest indication yet which species this individual belonged to.

The skull is not yet definitively confirmed as Homo heidelbergensis, but this could be confirmed in a future study.

Homo heidelbergensis lived between 300,000 and 600,000 years ago, evolving in Africa but by 500,000 years ago some populations situated in Europe.

The species was adept enough to hunt large animals for food, while the hides may also have been mad use of especially in colder areas.