Share this @internewscast.com

“When my children head to school, I find myself searching for electricity just to prepare a meal,” says Bernadette Angus.

Bernadette Angus and her family often huddle together in a single air-conditioned room with the curtains drawn, attempting to conserve their prepaid electricity on sweltering days. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

In Angus’s secluded Western Australian community, residents don’t get traditional electricity bills.

When their credit depletes, the power shuts off immediately, offering no warning, grace period, or safety net—just a bit of emergency credit that swiftly becomes debt.

According to Angus, a single day’s electricity costs about $20, but during the hotter months, this expense can easily double or even triple.

A daily countdown

On hot days, Shadforth carefully rations her electricity — choosing between cooling her home and keeping her freezer running.

Residents of Djarindjin face a unique struggle for energy security, as they are isolated from the major power grids and consumer protections. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

When asked how she feels about the choice, Shadforth says: “Oh, all depressed, you know.”

“We had power all night, then about 9pm it went off. By 8.40pm, we were hurrying to look for power … to look for some money to pay for power. That only gave me like what, [a] few minutes.”

Audrey Shadforth inside her home in Djarindjin, where she often has to choose between powering her air conditioner to stay cool and keeping her freezer cold. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

For Shadforth, each day feels like a countdown — one that resets only when there’s enough money to top up again.

‘No safety net’

But while city regulators, overseeing similar prepaid models in urban areas, have decided it would be too harsh to cut people off from electricity when their credit runs out, regulators in remote communities have prioritised ensuring bills are paid, rather than protecting people’s right to power.

(Left to right) The Original Power research team, Thomas Longden, Lauren Mellor, Lloyd Pigram, and Kathryn Thorburn. Their research focuses on the challenges faced by First Nations’ communities with prepayment energy meters. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

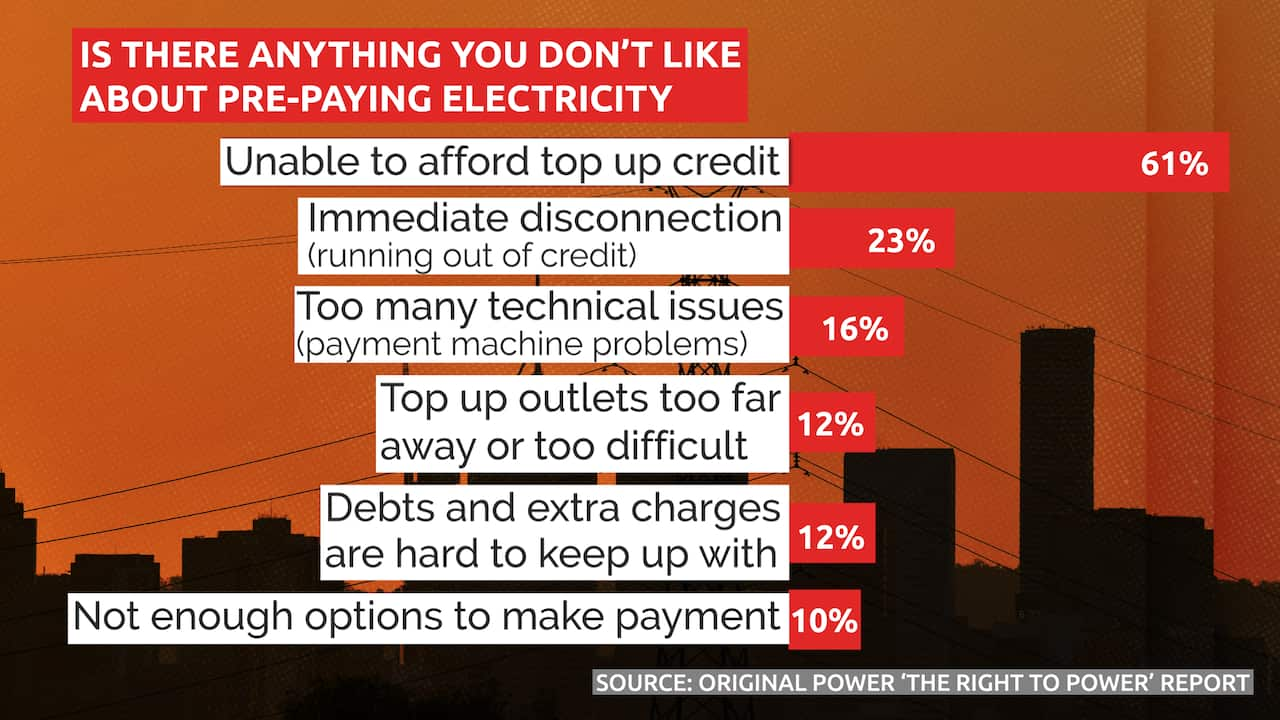

A new report released by Original Power, in partnership with Notre Dame’s Nulungu Research Institute and Western Sydney University, has shed light on the scale of the problem.

This resulted in average annual household expenditures of about $2,500 in the Northern Territory, $3,400 in Western Australia and $1,800 in South Australia.

“When you’ve got family and you are understanding that sort of stuff is happening around you … it’s hard not to get emotional or angry because you’re seeing people struggling.”

Some with not long left to live — and they’re still being disconnected from power.

Poor housing design and low energy efficiency can also drive up costs, Pigram explains. Many social homes in remote communities are poorly insulated and rely on old or inefficient appliances, which makes it far more expensive to keep houses cool in summer or warm in winter.

In homes where residents manage chronic illness, every essential — from medicine to temperature control — is placed at risk by the constant threat of prepaid power cuts. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

“It’s a system that puts the risk back on the individual,” Pigram says.

“If you run out of money, the power’s cut instantly — there’s no safety net.”

Climate, distance and deadly consequences

No electricity means no refrigeration for food or medicine, no fans or air-conditioning to help with heat stress, and limited access to communication or safety information during heatwaves and cyclones.

Appliances are essential for health in the Kimberley, but are the first items to be rationed when prepaid electricity credit runs low. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

The federal government’s National Climate Risk Assessment, released in September, named the Kimberley as one of Australia’s most climate-vulnerable regions and warned poor housing quality and isolation compound the risks.

It also urges governments to trial a summer protection scheme, ensuring prepaid households remain connected during dangerously hot weather, with lost revenue reimbursed through public funding.

The stark reality of prepaid electricity: Six in 10 people surveyed by Original Power said they struggle to simply afford the top-up credit. Source: SBS News

The report estimates the total annual cost of keeping those households connected during extreme heat across the NT, WA and SA is around $1.57 million — a figure that represents up to 95 per cent of the National Energy Bill Relief Fund expenditure for the same period.

Urgent calls for reforms from all sectors

“We’re working to make sure all communities get a fairer deal, and can share in the benefits of Australia’s renewable future.”

A store worker in Ardyaloon hands a piece of chocolate to a child. It’s in stores like these where prepaid households buy credits over the counter to apply the top-up. Source: SBS News / Christopher Tan

However, Bowen said regulation of off-grid systems remains the responsibility of state and territory governments.

“Since taking responsibility for electricity in 117 remote Aboriginal communities, Horizon Power has been rolling out advanced metering technology to regularise power supply, improve safety, and give customers more choice and control over their energy,” the spokesperson said.

This is a long-term commitment to Closing the Gap, ensuring every community, no matter how remote, has access to safe, reliable and affordable power.

The Northern Territory government said it would also review the report and “consider any recommendations that help improve coordination or simplify the application process” for relief programs.

“While Horizon Power is broadly supportive of the intent of the Original Power report, its recommendations deal with policy matters, and it would not be appropriate for Horizon Power, as a Government Trading Enterprise, to provide any comment.”

Community support

“Even today, someone caught a turtle and we all went there, bring us up, to come over for a feed. So nobody starves.”