Share this @internewscast.com

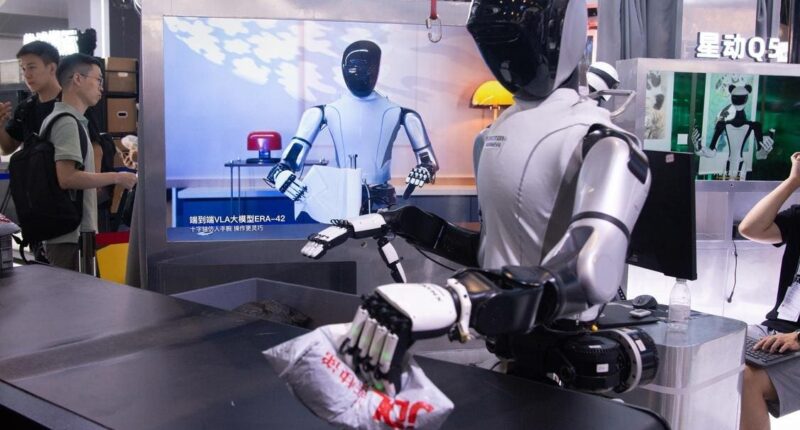

As factories around the globe wrap up their budgeting for 2026, they are confronted with a significant decision: Should they allocate funds to the development of humanoid robots that are making headlines, or invest in purpose-built systems that promise tangible returns on investment?

In the realm of space exploration, astronauts aboard the International Space Station frequently encounter the challenge of needing additional hands during spacewalks. However, NASA’s solution does not involve humanoid robots. Instead, the space agency has employed Canadarm2 and Dextre—sophisticated, two-armed manipulators equipped with specialized end effectors that operate efficiently around the clock. These systems are designed to enhance human capabilities, rather than imitate human form. Meanwhile, on Earth, billions of dollars in venture capital are being funneled into companies developing bipedal humanoid robots, aiming to mimic human appearance and movement, albeit often falling short.

During CES 2025, NVIDIA CEO Jensen Huang described physical AI as “the next big thing,” predicting that humanoid robots could revolutionize the $50 trillion manufacturing and logistics sectors. Goldman Sachs anticipates a market worth $154 billion by 2035. Various experts and contributors at Forbes express optimism, with Ethan Karp and Cornelia Walther noting the potential opportunities, and Bernard Marr forecasting a cultural shift due to robotics. However, Dev Patnaik raises concerns about societal acceptance, particularly in domestic settings. According to the Manufacturing Leadership Council, 22% of manufacturers plan to implement humanoid robots within the next two years. Despite this enthusiasm, the International Federation of Robotics recently questioned whether humanoid robots present a viable and scalable business model for industrial purposes.

Rodney Brooks, co-founder of iRobot and MIT professor emeritus, offered a stark critique in September 2025, dismissing the notion of humanoid robots achieving dexterity through video-based learning as “pure fantasy thinking.” Brooks highlights the technological gap, noting that while human hands are equipped with approximately 17,000 specialized tactile receptors, humanoid robots possess virtually none. The infrastructure necessary for gathering high-fidelity haptic data—akin to an ImageNet for touch—remains undeveloped. As a result, every malfunction in humanoid robots can lead to extended downtimes, increased liability, and retraining costs, which are conveniently omitted from slick promotional presentations.

The Reality Check From Robotics Pioneers

The issues extend beyond mere sensor technology. According to Yann LeCun, Meta’s Chief AI Scientist, genuine machine intelligence hinges on the creation of internal “world models” to anticipate physical outcomes. A welding robot, for instance, requires a model of its workspace on a millimeter scale. Conversely, humanoid robots aiming for general-purpose tasks must model the entire world, essentially trying to master an entire library of physics when factories need precision in just one chapter.

Safety is another critical concern. After witnessing a full-size bipedal humanoid robot topple over at close range, Brooks instituted a personal “three-meter rule” for safety. The potential risks multiply with the size of robots; a robot double the current size possesses eight times the destructive kinetic energy. Regulatory bodies have yet to establish safety protocols for bipedal humanoid robots navigating shared workspaces unpredictably, resulting in compliance challenges that could delay their widespread deployment.

Then there’s safety. Brooks instituted a personal “three-meter rule” after witnessing a full-size bipedal humanoid robot fall at close range. When they fail—and they will—the consequences scale exponentially. A robot twice current size packs eight times the destructive kinetic energy. Regulators have no established safety envelopes for bipedal humanoid robots moving unpredictably through shared workspaces, creating compliance friction that delays deployment.

The Form Factor Fallacy of Humanoid Robots

The assumption driving humanoid robot investment is seductive: humans designed factories for human bodies, so human-shaped robots slot directly into existing infrastructure. But this inverts the design challenge. We need robots that accomplish tasks humans struggle with, in conditions humans find difficult, with performance humans can’t match.

Consider deployed alternatives: Boston Dynamics’ Spot quadruped operates in oil platforms and automotive lines with stability bipedal humanoid robots can’t achieve. Universal Robots’ UR15 demonstrates AI-driven motion without humanoid bodies. Dextre, the Canadian robot that maintains the International Space Station since 2008 uses two seven-joint arms—one for stability, one for work—without wasting energy on bipedal balance.

Toyota’s robotics philosophy prioritizes incremental, purpose-built systems over humanoid robot moonshots. While Hyundai has announced future humanoid robot experiments, their Factory of the Future production systems today rely on autonomous mobile robots and collaborative arms—proven technologies delivering ROI now, not promises for later. These aren’t companies afraid of automation; they understand the difference between PR and production economics.

The economics are stark. Major humanoid robot vendors avoid discussing costs, but industry estimates place unit costs at $120,000-$200,000. Collaborative arms and autonomous mobile robots cost 40-60% less with established maintenance supply chains. Specialized systems achieve 95%+ uptime while humanoid robots face mechanical stress from bipedal locomotion that degrades components cyclically. Typical AMRs run 20-22 hours daily with predictable maintenance. No humanoid robots on the market achieve anything close.

Manufacturing Needs Non-Humanoid Robots

Physical AI represents genuine progress—just not through humanoid robots. The World Economic Forum analysis shows Amazon scales robotic arms and mobile robots across 300+ fulfillment centers, achieving 25% efficiency gains. Foxconn uses AI and digital twins for precision tasks, cutting deployment time 40%. The breakthrough isn’t humanoid robot form—it’s intelligence applied to task-specific systems.

Before committing capital to any physical AI system, executives should apply three tests: Does it extend human capability or reproduce it? Is the form factor minimum necessary? Can you quantify ROI within 18 months? If humanoid robot form is required to answer yes to all three, buy it. Otherwise, you’re paying what I call the Generalization Tax—the massive overhead of building humanoid robots that do 1,000 tasks poorly instead of 10 tasks perfectly. If a system fails any test, it’s speculation—not a manufacturing asset.

The Species We Already Have

The humanoid robot obsession isn’t irrational. After large language models plateaued in mid-2025, the AI industry correctly identified that physical intelligence requires embodied learning. The error is assuming humanoid robot embodiment is the only path.

But there’s a deeper fallacy: Earth hosts 8 billion humans who reproduce reliably, train adaptably, and excel at general-purpose problem-solving. If the goal is beings that look human and think human, we have abundant supply. What manufacturing needs are systems that perform tasks humans cannot do, cannot do safely, or cannot do economically at scale. We don’t need artificial humans. We need superhuman specialists.

This is the key psychological dimension: purpose-built machines are non-threatening amplifiers. Spot and Canadarm2 remain “suitably inferior” in their obvious machine-ness, amplifying human capability without threatening our sense of specialness. Humanoid robots that approach but never achieve human capability force us to question what makes us special if it can be mechanically reproduced—a feeling that degrades workplace trust and collaboration.

The Dynasphere, 1938. The Dynasphere was a monowheel vehicle patented by JA Purves in 1930. Churchman’s cigarette card, from a series titled Modern Wonders [WA & AC Churchman, Great Britain & Ireland, 1938]. (Photo by The Print Collector/Getty Images)

Getty Images

Consider what this reveals: the most transformative tools in history—the wheel, the lever, the computer—succeeded precisely because they didn’t replicate human form. They extended human capability into domains our biology couldn’t reach.

Manufacturing executives must recognize this isn’t just ROI calculation. It’s a choice about what role humans play in production. Do we design systems that let humans manage complexity with superhuman tools? Or chase human-shaped machines that promise to make humans optional?

Every dollar spent chasing humanoid robot generalization is a dollar not spent eliminating bottlenecks, removing hazards, or accelerating cycle time. As 2026 budgets lock in, manufacturers face choices with decade-long consequences. Choose tools that extend reach, not toys that reproduce form. In manufacturing, imitation isn’t innovation—it’s an avoidable cost.

We don’t need more humans. We have billions. We need machines designed for what humans can’t do—not humanoid robots dressed up to look like what we can. The future belongs to machines that make humans more capable, not more replaceable. Your investment decision reveals which future you’re building.

Trond Undheim is author of “The Platinum Workforce” (Anthem Press, 2025) and former Research Scholar at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation, and a humanoid robots skeptic.