Share this @internewscast.com

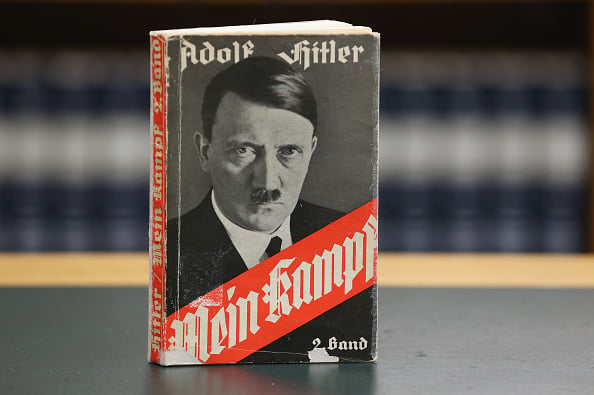

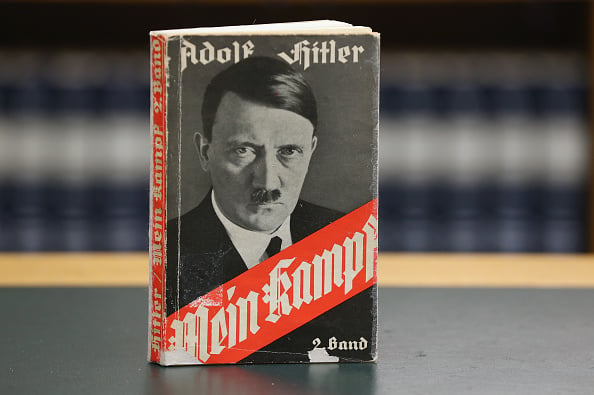

Unbeknownst to many, Adolf Hitler, notorious for his catastrophic impact on history, was also one of the wealthiest authors of his time. His book, “Mein Kampf,” not only catapulted him into political prominence but also filled his coffers, enabling the early Nazi Party’s ascension. Through the sale of over 10 million copies during his lifetime, Hitler amassed a substantial fortune. This wealth funded his extravagant lifestyle, which included a collection of custom Mercedes-Benz cars and opulent mansions throughout Germany.

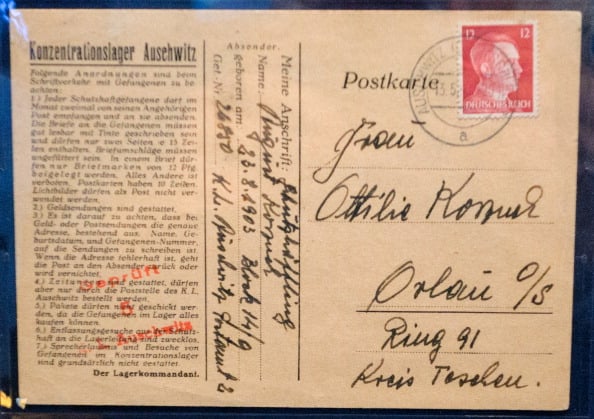

In addition to book royalties, Hitler profited immensely by licensing his likeness to the German government. His image was used extensively on postage stamps and political propaganda material. While the Nazi regime also exploited stolen art and treasures, this article focuses on Hitler’s earnings from his “legal” ventures during his lifetime.

The topic of Hitler’s royalties from “Mein Kampf” is surprisingly pertinent today, particularly with the rise of digital reading platforms like Amazon Kindle and Apple iPad. Astonishingly, “Mein Kampf” has achieved e-book bestseller status multiple times. In the early 2010s, a digital version priced at $1 by a Brazilian publisher soared to number one on Amazon’s “Propaganda & Spin” chart and reached the second spot in the “Political Science” category.

This resurgence in electronic format is often likened to the discreet consumption of controversial titles like “Fifty Shades of Grey.” E-books allow readers to privately engage with such material, circumventing the social stigma of being seen with a physical copy of “Mein Kampf.” This raises intriguing questions about who benefits from the book’s modern popularity. Are there descendants of Hitler today whose lifestyles are subsidized by these sales?

Who is cashing Mein Kamp royalty checks today?

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Why Did Hitler Write Mein Kampf?

Hitler penned “Mein Kampf” in 1923, while imprisoned in Landsberg after the Beer Hall Putsch’s failure. Dictated to fellow inmates Rudolf Hess and Emil Maurice, the book was initially conceived as a means to alleviate his legal debts. At that time, Hitler had modest hopes, aiming primarily to attract National Socialist Party supporters and secure a minor income stream.

Hitler Becomes A Millionaire

In 1925, the book’s debut year, it sold about 9,000 copies, generating no royalties for Hitler. However, as his political influence grew, so did book sales. By 1930, amid the Nazis’ rise in the Reichstag, sales reached 55,000. In 1933, the year Hitler was appointed Chancellor, sales surged to over 850,000 copies, cementing his financial and political dominance.

Once he held the reins of power, the German government effectively became Hitler’s largest customer. The state purchased and distributed millions of copies to soldiers and average citizens. Perhaps most famously, every married couple in Germany was given a “free” copy of the book on their wedding day—a gift paid for by the German taxpayer that funneled direct royalties into Hitler’s pockets.

At his peak, Hitler was earning over $1 million a year from “Mein Kampf” royalties. In the purchasing power of 2026, that is the equivalent of roughly $23 million a year. In total, by the time he committed suicide in 1945, Hitler had earned 7.8 million Reichsmarks from book sales. When adjusted for his “wealth status” and the relative size of the economy, that fortune is equal to roughly $220 million in 2026 US dollars.

Hitler used this fortune to fund a decadent lifestyle. He earned enough from his royalties to accumulate a tax bill that today would be worth over $15 million, which he promptly “forgave” through a retroactive tax exemption the moment he became Chancellor. While he was still a “struggling” politician, Hitler once wrote to a Mercedes-Benz dealer in Munich, asking for a loan against future royalties so he could buy the Mercedes 11/40 model. The dealer declined. Only a few years later, Hitler would own a fleet of custom-built Mercedes. He also invested millions of his own dollars into purchasing and renovating the Berghof property, transforming it from a small mountain chalet into a massive, high-tech estate with screening rooms, libraries, and tennis courts.

Heinrich Hoffmann/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Mein Kampf’s International Royalties

Hitler also earned royalties from international book sales up until 1939. While the amounts were more modest, they were not negligible. Between 1933 and 1938, his UK royalties amounted to roughly $500,000 in today’s money. In 1939, the United States government intervened by invoking the “Trading with the Enemy Act”, seizing control of all of Hitler’s US publishing royalties. By the end of the war, the US had seized approximately $255,000 (roughly $5 million in 2026 dollars) and eventually distributed the funds to war refugee charities.

Sean Gallup/Getty Images

Who Makes Money off Hitler’s Royalties Today?

When Hitler committed suicide in 1945, his nephew Leo Raubal (the son of Hitler’s half-sister) was technically his heir. Leo had a legitimate legal claim to the royalties, which even then were worth millions. However, Leo adamantly refused to touch a single cent of “blood money.”

Consequently, the copyright to “Mein Kampf” was seized by the State of Bavaria, where Hitler was officially a resident. For 70 years, Bavaria successfully used its copyright to block the publication of the book in Germany. However, under German law, copyrights expire 70 years after the author’s death. On January 1, 2016, “Mein Kampf” officially entered the public domain.

Today, anyone with a printing press or a digital publishing account can sell the book. In the United States, the rights were owned for decades by Houghton Mifflin, which faced immense public pressure regarding their profits. For years, they donated their royalties to organizations like the Anti-Defamation League. Today, most mainstream publishers follow this ethical standard, ensuring that profits from the book are used for education and Holocaust remembrance. However, the same cannot be said for the hundreds of “independent” publishers on the Kindle store who simply pocket the proceeds from their $0.99 versions.

Other Sources of Hitler’s Income

Hitler earned additional tens of millions of dollars licensing his image to the state for political purposes. During his reign, Hitler allowed his face to be used on German stamps and posters that fueled the Nazi propaganda machine. He did not provide this service for free. While the German photographer Heinrich Hoffmann technically owned the rights to Hitler’s official state portraits, most historians agree that Hoffmann acted as a proxy for the Führer himself. As with the rights to “Mein Kampf”, the rights to his image were eventually controlled by the State of Bavaria, with any residual profits directed toward charity.

PAUL J. RICHARDS/AFP/Getty Images

Furthermore, Hitler’s early career as a painter in Vienna left behind hundreds of watercolours. While the US government seized many of these after the war, some remain in private hands. Today, a single Hitler painting can fetch $30,000 to $50,000 at auction. While Hitler’s surviving distant relatives (who live under assumed names today) could technically claim these assets, they have maintained a strict “pact of silence,” refusing to ever profit from their ancestor’s name.

BEHROUZ MEHRI/AFP/Getty Images

In Conclusion

History must remember that Hitler’s rise was not just fueled by rhetoric, but by a massive financial engine built on the sales of “Mein Kampf”. The book made him a multi-millionaire before he even became a dictator. Today, the book remains a bestseller in the digital shadows, but in an ultimate irony, the “legal” royalties from his work now serve to fund the very humanitarian and Jewish charities that Hitler dedicated his life to destroying. For every digital copy sold by a legitimate publisher today, a few cents are likely going toward ensuring his ideology never rises again.

(function() {

var _fbq = window._fbq || (window._fbq = []);

if (!_fbq.loaded) {

var fbds = document.createElement(‘script’);

fbds.async = true;

fbds.src=”

var s = document.getElementsByTagName(‘script’)[0];

s.parentNode.insertBefore(fbds, s);

_fbq.loaded = true;

}

_fbq.push([‘addPixelId’, ‘1471602713096627’]);

})();

window._fbq = window._fbq || [];

window._fbq.push([‘track’, ‘PixelInitialized’, {}]);