Share this @internewscast.com

Nvidia was in the spotlight as it unveiled its latest financial results, capturing the attention of the global market.

Investors, already on edge due to recent market fluctuations, were keen to see if the $4.5 trillion company, a central player in the AI surge, would meet expectations.

If Nvidia’s earnings surpassed predictions, it would keep the stock market momentum alive. However, falling short could lead to a significant market downturn.

Nvidia delivered impressive results, reporting third-quarter revenues of $57 billion (£44 billion) and forecasting $65 billion (£50 billion) for the upcoming quarter, exceeding expectations.

While investors found relief in Nvidia’s strong performance, many still ponder the timing of a potential AI market correction, asking, “If not now, when?”

Nvidia’s meteoric rise and the lofty expectations for U.S. tech stocks suggest that any future disappointment could spark a market crash.

Nvidia has grown so much that the company is worth 50 per cent more than the combined valuation of the 100 firms that make up the FTSE 100, the UK’s leading stock market index.

And with so many UK investors holding tracker funds that leave them dependent on the US tech giant-dominated global stock market’s fortunes, this would severely dent the pensions and investments of millions of Britons.

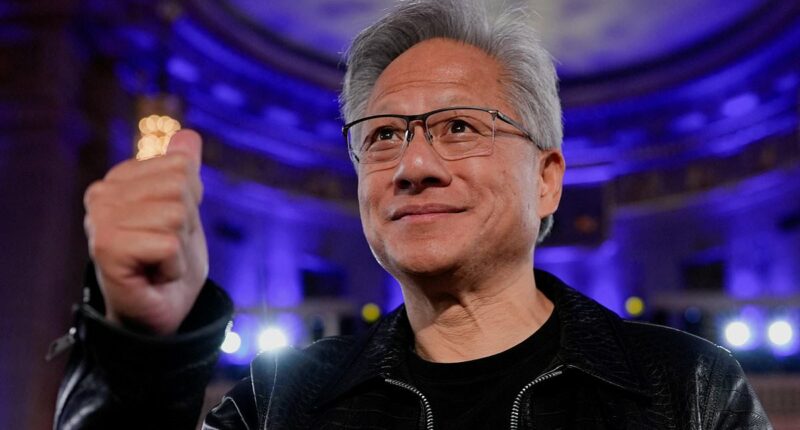

Nvidia boss Jensen Huang has seen his company become the most valuable in the world

Nvidia’s results in a nutshell

Nvidia reported another set of record-breaking results after the New York stock market closed.

The AI computer chip giant was expected to deliver an astonishing $55billion (£42billion) in revenue in its third quarter earnings, up 56 per cent on a year ago.

But crucially Wall Street was also looking for its projected sales for next quarter, which were expected to be an even more gargantuan – at $62billion (£48billion).

In crowd-pleasing results, Nvidia said in the third quarter of the year it raked in $57billion in sales in just three months – and that will grow to $65billion in this quarter.

Its data centre segment revenues, which account for most of the chip designer’s revenue, came in at $51billion.

Stephen Yiu, manager of the Blue Whale Growth fund, which holds a large position in Nvidia, says the company isn’t in an AI bubble:

He says: ‘Whilst there are dot-com era bubbly valuations among private AI companies such as OpenAI and Anthropic, Nvidia’s valuation remains attractive at a 30x one-year forward P/E ratio, with a 50 per cent free cash flow margin.’

Nvidia boss Jensen Huang said that sales of its key Blackwell chip were ‘off the charts’, cheering analysts and investors. Shares immediately bounced and climbed 5 per cent in after hours trading. However, in the first few hours of trading today they slipped 1.2 per cent.

Matt Britzman, senior equity analyst at Hargreaves Lansdown, said: ‘Nvidia bears the weight of the world but, like Atlas, it’s standing firm under that towering mountain of expectations. Third quarter results delivered the goods and then some.’

How Nvidia became the world’s most important company

So just how did a quarterly earnings report from a tech company, which few outside Silicon Valley and Wall Street had heard of until recently, become so pivotal to the fortunes of global stock markets – and the value of your pension pot?

To answer that question you need to understand the key role Nvidia – and its chief executive Jensen Huang – played in the AI revolution.

Nvidia is the brainchild of Huang – a Taiwan-born electrical engineering graduate whose parents sent him to the US as a child – and two veteran microchip designers, Chris Malachowsky and Curtis Priem.

They founded the company in 1993 at a Denny’s restaurant in San Jose, California.

Huang – who once worked as a Denny’s dishwasher earning $2.65 an hour – has run the company ever since and is now one of the world’s richest people, with an estimated net worth of $158billion (£121billion), according to the latest Bloomberg Billionaires index.

Nvidia’s main product is its graphics-processing unit (GPU), a tiny circuit board with a powerful microchip at its core that can handle complex calculations and repetitive tasks simultaneously – and at much faster speeds than rivals.

Originally designed for video games, these processors proved ideal for the so-called ‘fourth industrial revolution’ that AI heralds.

Nvidia’s chips provide the enormous computing power within physical data centres that store and retrieve vast quantities of text and video from the internet, as well as other sources, used to train chatbots and other large language models.

Unlike rivals such as Intel, Nvidia doesn’t actually make these chips. They are mainly contracted out to the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC).

But crucially, Nvidia not only designs the hardware – the microchips – but also the software on which they run.

After successful trials of its Coda software platform, Huang went all-in on AI in 2013. He has not looked back since.

The emergence of OpenAI’s ground-breaking ChatGPT sent Nvidia shares into orbit

Nvidia really came of age a decade later when it emerged that ChatGPT – Open AI’s ground-breaking chatbot – was powered by its most sophisticated chips.

The news sent Nvidia’s shares into orbit, as big tech companies and AI start-ups alike scrambled to get their hands on its processors. To meet the insatiable demand Nvidia launched a new generation of high-end AI chips – codenamed Blackwell – costing more than $30,000 each.

Nvidia can charge so much because of it has cornered the market in AI chips. Its near monopoly has turned the company into a massive money-making machine and propelled a share price surge unmatched in stock market history.

Over the past five years, Nvidia shares have soared 1,300 per cent.

Nvidia became the fastest company ever to go from a $1trn to a $2trn valuation. Astonishingly, it took just eight months.

Then four months later, on June 18, 2024, Nvidia vaulted fellow tech titan Microsoft to become the world’s most valuable firm.

And last month another milestone was hit when Nvidia’s stock market valuation topped $5trillion (£3.8trn) – more than the entire annual output of Germany, the world’s third largest economy.

Neil Wilson, of Saxo Markets, says that while there was a huge market focus on Nvidia’s latest results, it is not necessarily the chip designer that people need to look to when considering the AI bubble.

Nvidia is benefitting from massive demand, whereas what will constrain the AI gold rush is the huge demand for electricity and whether chips can be delivered fast enough.

On the Nvidia results, he commented: ‘Hard to find much here changes the story, as we knew beforehand that AI demand is insatiable and hyperscalers are still spending big.

‘The questions over AI will not be answered this quarter or until one to 2 years: a) is there enough cash, b) can it be deployed (energy), and c) can it be deployed with any semblance of efficiency. Backlog rose, constraints are in power and supply, not in demand.’

Why investors fear an AI bubble bursting

Like all new technologies, investors are attracted to AI by the prospect of lower production costs – and higher profits – as many traditional white-collar jobs are rendered obsolete by automation.

But the sheer amount of money now pouring into AI has fuelled concerns they may never see a return on their investment.

Eyebrows have been raised by a string of recent complex deals between ChatGPT creator Open AI and the likes of Nvidia, Microsoft and software giant Oracle worth $1.4trillion (£1.1trillion) in total – even though Open AI only has revenues of just $13billion.

Warnings that the AI boom could turn to bust abound, from the Bank of England to the International Monetary Fund.

Jamie Dimon, boss of the world’s biggest bank JP Morgan, thinks that some of the cash being showered on the sector will ‘probably be lost’.

And Sundar Pichai, who runs Google-owner Alphabet, reckons ‘no company is going to be immune’ if the AI bubble bursts.

They fear a repeat of the dotcom crash a quarter of a century ago, when the internet was still in its infancy.

While many of today’s AI giants are making huge profits – as in 2000, the valuations of some tech companies today look stretched in the extreme. If they fail to meet lofty earnings expectations their shares could fall a long way.

The difference is that far more wealth is tied up in tech stocks today than it was back then. The so-called Magnificent 7 – Nvidia, Apple, Amazon, Microsoft, Facebook-owner Meta, Alphabet and Tesla – account for more than a third of the benchmark S&P 500 index total value.

Meanwhile, the US stock market accounts for about 70 per cent of the global MSCI index.

In other words, when the tech giants sneeze, global stock markets catch a cold, wiping billions off the value of pensions and investments.

There are concerns that the widespread use of exchange traded funds (ETFs), which track the market up and down, could add to selling pressure if investors pull their cash out in a rush and exacerbate a crash.

As Rich Privorotsk, a partner at investment bank Goldman Sachs put it recently: ‘There are just a lot of things about this market that haven’t been adding up for a while. We have been overdue a correction and the question is the magnitude.’

The big investors ditching Nvidia

Some shareholders in Nvidia have already voted with their feet. Two major technology investors – Japanese conglomerate Softbank and American entrepreneur Peter Thiel – have recently dumped their entire stakes in the company

And earlier this month Michael Burry – the ‘Big Short’ investor who famously anticipated the US housing crash ahead of the 2008 financial crisis – disclosed a big bet his hedge fund had made on Nvidia’s share price falling, along with fellow tech high-flier Palantir’s shares.

The timing of these moves may be coincidental, but it did little to soothe investors’ nerves that a blow-up was imminent.

Ahead of the earnings announcement Nvidia had lost around $600billion (£460billion) – about 11 per cent of its value – since its share price peaked at the end of last month. Other tech stocks have fared worse, notably Oracle, down almost a fifth from its recent high.

The AI believers

For now, though, AI believers are keeping the faith.

Stephen Yiu, of Blue Whale, notes ‘not all bubbles are the same’ and argues ‘AI is already delivering’.

He cites the example of the dotcom bubble, which saw the mass adoption of the internet and mobile phones but also ‘a lot of friction’ because ‘the technology was still in its infancy, hampered by slow data speeds and basic handsets’.

Compare that, he says, with how quickly ChatGPT was adopted to reach 800 million users in only three years, whereas the internet took 13 years to reach the same number.

The tangible impact on our work and personal lives that AI is already having justifies the huge sums being pumped into the technology by the tech giants, Yiu adds.

But even he is cautious: ‘If that tilts the other way, and investment outweighs the value added by AI, that’s when a bubble could form.’

Will the AI bubble turn into a crash?

Nvidia’s results may settle investors’ nerves after a febrile month saw sentiment shift from companies and markets hitting new highs, to sizeable share price falls and worries a correction had begun.

But the results are likely to stall fears rather than make them go away. Some firms, such as Nvidia, remain massively profitable but investors’ expectations are sky-high and there will come a point when they can’t be delivered on.

The race to build massive power-guzzling datacentres in the US to service the AI boom has led to a number of tech firms being dubbed ‘hyperscalers’, as they rush headlong into building capacity.

But critics raise concerns ranging from the remote locations of some data centres, to whether enough electricity can be generated to power them, how long expensive chips will remain cutting edge, and the circular deals being struck between companies.

Increasing numbers of investors believe we are in a bubble and are nervously waiting for the event that will pop it – sending tech stocks tumbling and the whole stock market into a correction.

DIY INVESTING PLATFORMS

AJ Bell

AJ Bell

Easy investing and ready-made portfolios

Hargreaves Lansdown

Hargreaves Lansdown

Free fund dealing and investment ideas

interactive investor

interactive investor

Flat-fee investing from £4.99 per month

Freetrade

Freetrade

Investing Isa now free on basic plan

Trading 212

Trading 212

Free share dealing and no account fee

Affiliate links: If you take out a product This is Money may earn a commission. These deals are chosen by our editorial team, as we think they are worth highlighting. This does not affect our editorial independence.

Compare the best investing account for you