Share this @internewscast.com

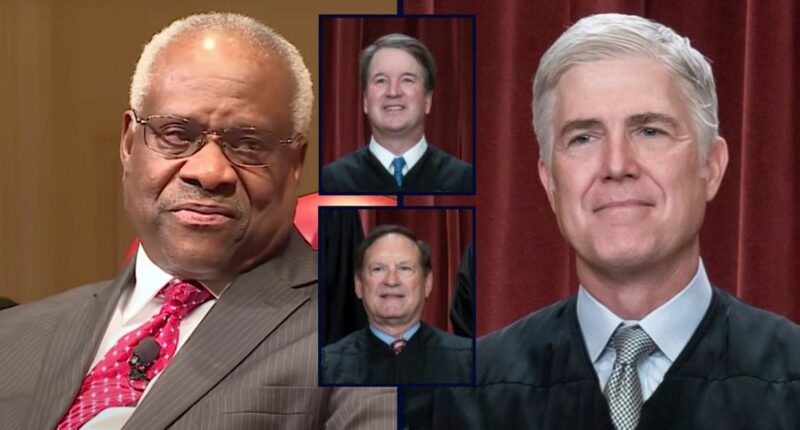

Left to right: Clarence Thomas (Library of Congress/YouTube) and Neil Gorsuch (Erin Schaff-Pool/Getty Images). Inset top to bottom: Brett Kavanaugh and Samuel Alito (Alex Wong/Getty images).

In a pivotal decision that sent waves through the financial markets, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled on Friday to curtail the president’s unilateral ability to impose tariffs, deeming it an unconstitutional tax. This landmark ruling casts doubt over the entire trade strategy employed during the Trump administration, causing significant surges in stock indices.

In a divided decision, the majority of the justices opted to restrict the president’s powers, an unusual stance for the Roberts Court. This long-awaited verdict, arising from the case Learning Resources v. Trump, was decided by a 6-3 margin. The ruling hinged on the argument that the International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) does not mention tariffs, that tariffs function as a form of taxation, and that the term “regulate” does not equate to the authority to impose taxes.

Justice Clarence Thomas, dissenting, challenged the fundamental terms of the debate by referring to import levies as “duties” rather than “tariffs” or “taxes,” to bolster his position. In Thomas’s view, the American colonists were not particularly troubled by “financial exactions” imposed by the British monarchy for trade regulation, provided these were not “internal” taxes aimed at raising revenue.

Thomas’s historical perspective, detailed in an extensive footnote, supports his broader argument that President Donald Trump’s use of tariffs does not violate the “separation of powers principles.”

To hear Thomas tell it, the colonists who would become the American revolutionaries did not much mind “financial exactions” from the British monarchy in the name of regulating trade and commerce so long as such efforts were not “internal” taxes to raise revenue.

This quick history lesson, contained in a lengthy footnote, is in service of the broader idea that President Donald Trump’s use of tariffs does not implicate “separation of powers principles.”

In the majority opinion, Chief Justice John Roberts cites the separation of powers to say that “Congress would not have delegated ‘highly consequential power’ through ambiguous language.”

That is to say, the IEEPA’s arguably vague grant of authority to “regulate…importation” cannot be used by the executive branch to claim a core congressional power like the “power of the purse.”

This is, at least in part, because of the nondelegation doctrine — which holds that while Congress can give away some powers to the other branches, “essential legislative functions” cannot be given away.

Thomas, however, rejects the use of the doctrine out of hand.

The key for the dissent is the external focus of the tariffs.

“The power to impose duties on imports can be delegated,” the dissent argues. “At the founding, that power was regarded as one of many powers over foreign commerce that could be delegated to the President. Power over foreign commerce was not within the core legislative power, and engaging in foreign commerce was regarded as a privilege rather than a right.”

Thomas goes on to say the nondelegation doctrine only applies to congressional “powers that implicate life, liberty, and property.”

Here, the dissent draws some very fine distinctions using a litany of examples. The nondelegable side contains laws that implicate internal taxes, counterfeiting, and treason on the one hand. The delegable side contains laws regarding military funding, copyrights, and foreign commerce on the other hand.

Speaking of the latter, Thomas says: “None of these powers involves setting the rules for the deprivation of core private rights.”

The dissent returns to history to make the argument that many congressional powers are just former powers of the British monarchy that the Founding Fathers decided to allocate to Congress.

Thomas then goes on to argue that the word “legislative” really only means “the power to make rules binding on persons or property within the nation,” saying this view likely accords with “the views of separation-of-powers theorists” during the founding of the nation.

“As a matter of original understanding, historical practice, and judicial precedent, the power to impose duties on imports is not within the core legislative power,” the dissent goes on. “Congress can therefore delegate the exercise of this power to the President.”

Thomas goes on like this, at length:

The power to impose duties on imports thus does not implicate either of the constitutional foundations for the nondelegation doctrine. Hence, even the strongest critics of delegation, myself included, have recognized that regulations of foreign commerce might not be subject to ordinary nondelegation limitations. …

Congress’s delegation here was constitutional. The statute at issue in these cases, the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, delegates to the President a wide range of powers over foreign commerce. IEEPA gives the President, on conditions satisfied here, the power to “regulate” foreign commerce, including “importation” of foreign property.

IEEPA’s delegation of power to impose duties on imports complies with the nondelegation doctrine.

The dissent continues on to argue that “[h]istorical practice and precedent” support the delegation of tariff powers to the president.

This argument dovetails with the other dissent penned by Justice Brett Kavanaugh — joined by Justice Samuel Alito and Thomas himself.

“The sole legal question here is whether, under IEEPA, tariffs are a means to ‘regulate…importation,’” Kavanaugh writes. “Statutory text, history, and precedent demonstrate that the answer is clearly yes: Like quotas and embargoes, tariffs are a traditional and common tool to regulate importation.”

While rejecting the application of the major questions doctrine, the Kavanaugh dissent turns to some of the logic of the Thomas dissent — in terms of using the foreign affairs nature of the debate to weigh in on the side of the executive branch.

“Presidents ‘have long been granted substantial discretion over tariffs,’” according to Kavanaugh. “This Court has never before applied the major questions doctrine to a statute authorizing the President to take action with respect to foreign affairs in general or tariffs in particular. And it should not do so today.”

In a lengthy concurrence, Justice Neil Gorsuch needles Kavanaugh and Alito as selective proponents of the major questions doctrine and skewers the Thomas dissent as “a sweeping theory” that stands for the proposition “Congress may hand over most of its constitutionally vested powers to the President completely and forever.”