Share this @internewscast.com

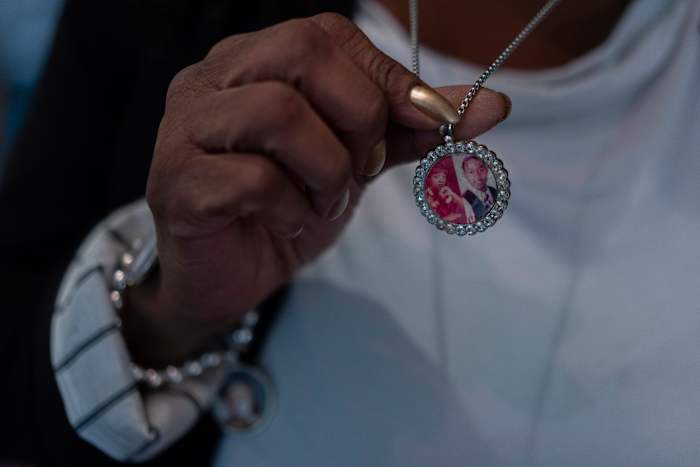

Delphine Cherry is acutely aware of how persistent violent crime is in Chicago. Her teenage daughter became a victim in a gang shootout in one of the city’s upscale neighborhoods back in 1992. Two decades later, her son was similarly lost to violence in a suburb just south of the city.

“You don’t think it’s going to happen twice in your life,” she said.

For weeks, Chicago has been anticipating President Donald Trump’s promised deployment of National Guard troops to the nation’s third-largest city. While Trump claimed the troops would combat crime in what he labeled a “hellhole,” his administration has been reticent regarding the operation’s specifics, including the commencement date, duration, troop numbers, and their role in civilian law enforcement.

Trump’s stance on sending troops to Chicago has been inconsistent — sometimes vowing unilateral action to deploy them, while at other times indicating a preference to send them to New Orleans or another city in a state where the governor “wants us to come in.” Most recently, he mentioned this week that Chicago is “probably next” after National Guard deployment to Memphis.

Even though Chicago has long had one of the highest rates of gun violence among major U.S. cities, city and state leaders largely oppose the proposed deployment, dismissing it as political theater. Those directly affected, including individuals who have lost loved ones to violent crime, question the long-term effectiveness of troop involvement against such violence.

In Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., troops acted as guards

With the details of the Chicago deployment still unclear, the use of National Guard troops in Los Angeles and Washington this past summer might offer some insights.

In June, Trump deployed thousands of Guard troops to Los Angeles amidst protests linked to his administration’s immigration policies. Initially tasked with guarding federal property, the troops later provided security for immigration agents during raids and participated in a forceful display at a park in a predominantly immigrant neighborhood of LA, which local officials believe was intended to instill fear.

In August, Trump announced he was placing Washington’s police force under his control and mobilizing federal forces to reduce crime and homelessness there. The troops who were deployed have patrolled around Metro stations and in the most tourist-heavy parts of the nation’s capital. But they have also been spotted picking up trash and raking leaves in city parks.

The White House reported that more than 2,100 arrests had been made in Washington in the first few weeks after Trump announced he was mobilizing federal forces. And Mayor Muriel Bowser credited the federal deployment with a drop in crime, including an 87% decline in carjackings, but also criticized the frequent immigration arrests by masked ICE agents. However, an unusually high rate of cases being dropped has some, including at least one judge, wondering whether prosecutors are making charging decisions before cases are properly investigated and vetted.

Washington is unique in that it is a federal district subject to laws giving Trump power to take over the local police force for up to 30 days. The decision to use troops to try to fight crime in other Democratic-controlled cities would represent an important escalation.

Chicago leaders call for more funding instead

Although the Trump administration hasn’t said what the troops would be doing and what parts of Chicago they would operate in, they have explicitly promised a surge of federal agents targeting immigration enforcement. The city’s so-called sanctuary policies are among the country’s strongest and bar local police from cooperating with federal immigration enforcement.

Chicago isn’t the only Democratic-led city in Trump’s sights — he’s also mentioned Baltimore as a likely target. But Trump seems to harbor particular scorn for the Windy City, warning in an “Apocalypse Now”-themed social media post earlier this month: “’I love the smell of deportations in the morning. Chicago about to find out why it’s called the Department of WAR.”

The president’s criticism, though, is more often focused on how the city’s and state’s Democratic leaders deal with crime.

Mayor Brandon Johnson and Illinois Gov. JB Pritzker have repeatedly pointed to a drop in crime in Chicago and have asked for more federal funding for prevention programs instead of sending in the National Guard.

Last year, the city had 573 homicides, or 21 per every 100,000 residents, according to the Rochester Institute of Technology. That’s 25% fewer than in 2020 and was a lower rate than several other major U.S. cities. Like most big cities, violent crime isn’t evenly spread out in Chicago, with most shootings happening on the South and West sides.

“If it was about safety, then the Trump administration would not have slashed $158 million in federal funding for violence prevention programs this year,” said Yolanda Androzzo, executive director of gun violence prevention nonprofit One Aim Illinois.

Victims of violent crime doubt troops can make lasting change

After Cherry’s 16-year-old daughter, Tyesa, was killed in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood by a stray bullet that a 14-year-old fired at rival gang members, the devastated mother moved her family to Hazel Crest, a suburb just south of the city.

“We were planning for prom. She was going on to college to be a nurse,” Cherry said.

Her son, Tyler, was fatally shot in the driveway of the family’s suburban home in 2012, 20 years after Tyesa was killed.

Although her children’s deaths have made Cherry an antiviolence advocate — she sits on One Aim Illinois’ board — she doesn’t believe bringing in troops will do anything to fight crime in Chicago, and that it could making the streets more dangerous.

“They’re not going to ask questions,” Cherry said of the National Guard. “They are trained to kill on sight.”

Trevon Bosley, who was 7 years old when his 18-year-old brother, Terrell, was shot and killed in 2006 while unloading drums outside of a Church before band rehearsal, also thinks sending in troops isn’t the answer.

“There is so much love and so much community in Chicago,” said Bosley, whose brother’s killing remains unsolved. “There are communities that need help. When those resources are provided, they become just as beautiful as downtown, just as beautiful as the North Side.”

Like Johnson, Pritzker and other critics of the promised troop deployment, Bosley thinks better funding would make a real positive difference in parts of the city with the highest crime and poverty rates.

“It’s not like we have a police shortage,” Bosley said. “The National Guard and police show up after a shooting has occurred. They don’t show up before. That’s not stopping or saving anyone.”

__

Associated Press reporter Christine Fernando contributed to this report.

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.