Share this @internewscast.com

NEW YORK – The plots of Dan Brown’s novels have so many turns that even the author has to make sure he can keep it all organized.

“Any author working on a thriller needs a solid plan. There’s a saying that a thriller writer who begins a book without direction is simply not being truthful,” he shared with The Associated Press on Tuesday.

“These novels are undoubtedly intricate. My strategy to manage this complexity is to write daily, which helps maintain clarity. If I miss a couple of nights of sleep cycles, it becomes elusive. Naturally, I also use what resembles a detective’s board at a police station. It’s filled with pictures, strings, notes, and sticky notes all plastered on my wall to keep everything organized.”

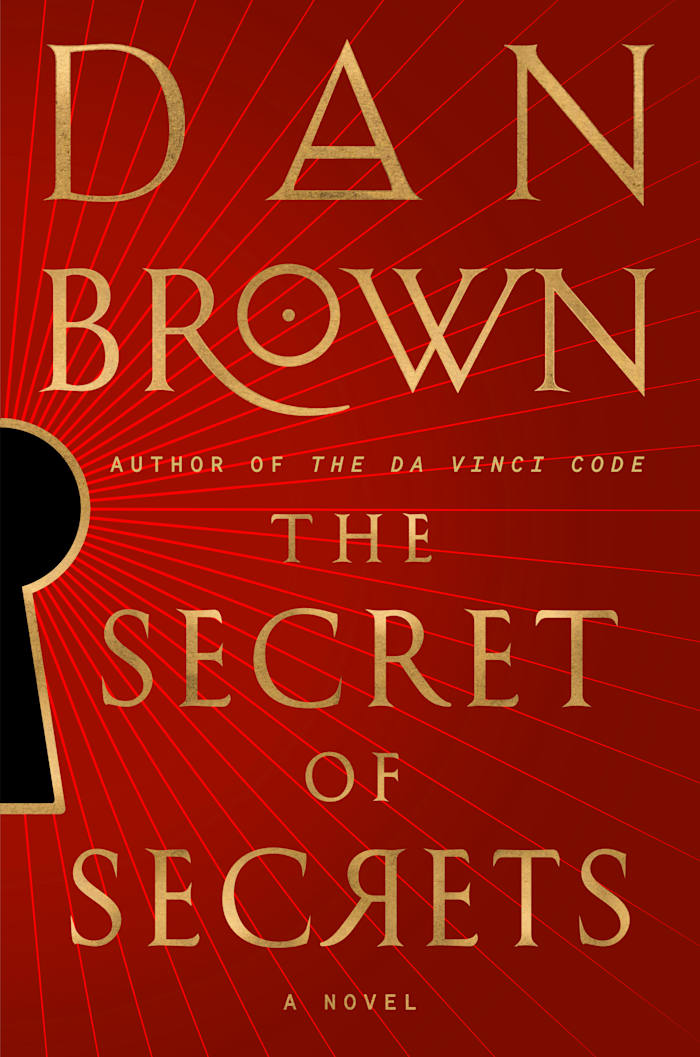

This week marks the release of Brown’s “The Secret of Secrets,” a 650-page intricate thriller from the mastermind recognized globally for “The Da Vinci Code,” “Angels & Demons,” and other major hits. Brown masterfully intertwines suspense, philosophical tangents, and travel descriptions, all while integrating codes, puzzles, and clandestine societies. He once more sends his beloved protagonist, Robert Langdon, on a mission to Prague, entangling him in a perilous international chase to uncover the ultimate truth — what occurs after death.

Besides Langdon, the Harvard symbologist known for encountering adventures and challenges from Paris to Washington, D.C., Brown reintroduces the love interest and distressed noetic scientist Katherine Solomon, alongside a New York-based book editor based on a real person. “Jonas Faukman” is an anagram for Brown’s editor at Doubleday Books, Jason Kaufman, who has collaborated with him for over two decades. Both claim a strong friendship, despite Brown’s portrayal of Faukman as a kidnapping victim in the new book.

“Receiving manuscripts from Dan is always exciting and intriguing,” Kaufman mentioned to the AP recently. “I prefer he doesn’t reveal his plans to me beforehand. He consistently finds ways to astonish me.”

Brown also discussed with the AP how he selects his themes, his shifting perspective on mortality, and why Prague serves as an ideal backdrop for conspiracies. The interview has been condensed and edited for clarity and conciseness.

____

AP: How do you go about deciding what to write about?

BROWN: It’s no secret that I like to write about big topics and there really is no topic that is bigger than consciousness. It is the lens through which we see ourselves. And so the real challenge was how to make a concrete urgent modern thriller about something that’s so ethereal.

About eight years ago, my mom passed away about the time that I was thinking of writing about consciousness, and I started asking myself, “What happens when we die?” and if you’d asked me eight years, ago, I’d say nothing It’s full stop total blackness. Over the course of the eight years that took me to write this book and all the conversations that I had with philosophers and physicists and noetic scientists, I’ve come out the other side with a totally different mindset. And in fact, it sounds crazy. I no longer fear death.

AP: Before you worked on this book, did you consider yourself an atheist? An agnostic? How would you have described yourself?

BROWN: I grew up Christian, Episcopalian, but I moved away from the organized nature of religion. I’ve always been spiritual and sensed there’s something else, but I’ve also been skeptical and said, “Well, that sense of there’s just something else could just be wishful thinking.” It could be because it’s so hard to imagine that there’s nothing else that we just sort of say, “Well, I sense there’s some thing else.”

And now I do sense there’s something else. And that is from an intellectual standpoint. I have not had a religious experience, a spiritual experience, an outer body experience, or near death experience. This change of mind comes from looking at the science that is happening right now in the world of physics and noetics.

AP: Some people talk about the creative process, so to speak, as almost a religious experience, that moment the idea comes to you, whether it’s the right phrase or a piece of music.

BROWN: It’s called flow, a muse. Certainly, we writers have that experience of, “Ah, I’ve got it. It’s just flowing through me.” I have certainly felt that. Not every day, unfortunately. There’s a lot of trial and error, but that is the feeling that creative people are always looking for. My mom was a professional musician. I was brought up to be a musician. I thought I would be a musician. I still play piano every day. I studied music composition in university, and I’ve had that experience also with music.

That sort of muse moment when something flows in, it’s different between writing and music. Writing sort of feels like finding the right Lego piece to put in. You say, “Ah.” It’s almost like doing a jigsaw puzzle. You’re like, “Got it. It fits.” And music is a little bit more fluid. It’s like making a big brush stroke. And the melody just sort of flows in and finds its way to your hands, and then it exists.

AP: The cities you set your books in are so important to what you do. Do you have a kind of wish list? Like, “I need to set a book in this city.”

BROWN: I mean, there are a few of them that I won’t mention because I don’t want people running out, and they’re sort of off the beaten path, kind of like Prague is.

I like to use location as a character. I want to make sure that, whatever book it is, it could only be set there. “The Lost Symbol” could only be set in D.C. because it’s about the symbology of D.C. “The Da Vinci Code” could only be set in Paris because it is about the Roseland. “The Secret of Secrets,” about human consciousness, could only be set in Prague. It’s been the mystical capital of Europe since Emperor Rudolf II (in the late 16th-early 17th centuries) brought all the mystics and scribes and alchemists to Prague. And as a character, Prague is perfect for Langdon. It’s full of secret passageways and cathedrals and monasteries and all, that’s his world.

AP: Puzzles and mystery and passageways, that’s just endlessly fascinating to you? It’s as interesting to you now as when you were 10 or 20?

BROWN: I don’t know what that says about me, but yeah, I still love secret passageways. You talk about that “aha” moment. It’s kind of the same thing to say, “Wait, there’s something here that you don’t see and now you see it.” It’s the same kind of sensation of “aha.”

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.