Share this @internewscast.com

(The Conversation) – The initial space race focused on national pride and making a mark, namely with flags and footprints. Now, many years after the first lunar landing, the new objective is to establish a presence on the Moon, and achieving this largely depends on energy solutions.

In April 2025, China revealed plans to construct a nuclear power facility on the Moon by 2035, aiming to support its envisioned international lunar research station. The United States followed by declaring in August that it aims to have a functional reactor on the Moon by 2030, as stated by acting NASA Administrator Sean Duffy.

Though this may seem like a recent rush, it has been underway quietly for years. NASA, alongside the Department of Energy, has been developing compact nuclear systems intended to power lunar outposts, mining ventures, and sustained human habitats.

From the perspective of a space law expert focused on the long-term human expansion into space, this can be viewed not as an arms race but as a battle for strategic infrastructure. In this scenario, infrastructure equates to influence.

While the idea of a nuclear reactor on the Moon sounds significant, it is neither unlawful nor unprecedented. If managed carefully, such reactors can provide nations with opportunities to explore the Moon peacefully, enhance their economies, and experiment with technologies for further space exploration. However, the development of these reactors also prompts crucial discussions about access and control.

The legal framework already exists

The concept of utilizing nuclear power in space is not revolutionary. Since the 1960s, both the U.S. and the Soviet Union have used radioisotope generators, which harness small quantities of nuclear material to power satellites, Mars rovers, and the Voyager space probes.

One great story in your inbox every afternoon

Try our Substack

The United Nations’ 1992 Principles Relevant to the Use of Nuclear Power Sources in Outer Space, a nonbinding resolution, recognizes that nuclear energy may be essential for missions where solar power is insufficient. This resolution sets guidelines for safety, transparency and international consultation.

Nothing in international law prohibits the peaceful use of nuclear power on the Moon. But what matters is how countries deploy it. And the first country to succeed could shape the norms for expectations, behaviors and legal interpretations related to lunar presence and influence.

Why being first matters

The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, ratified by all major spacefaring nations including the U.S., China and Russia, governs space activity. Its Article IX requires that states act with “due regard to the corresponding interests of all other States Parties.”

That statement means if one country places a nuclear reactor on the Moon, others must navigate around it, legally and physically. In effect, it draws a line on the lunar map. If the reactor anchors a larger, long-term facility, it could quietly shape what countries do and how their moves are interpreted legally, on the Moon and beyond.

Other articles in the Outer Space Treaty set similar boundaries on behavior, even as they encourage cooperation. They affirm that all countries have the right to freely explore and access the Moon and other celestial bodies, but they explicitly prohibit territorial claims or assertions of sovereignty.

At the same time, the treaty acknowledges that countries may establish installations such as bases — and with that, gain the power to limit access. While visits by other countries are encouraged as a transparency measure, they must be preceded by prior consultations. Effectively, this grants operators a degree of control over who can enter and when.

Building infrastructure is not staking a territorial claim. No one can own the Moon, but one country setting up a reactor could shape where and how others operate – functionally, if not legally.

Infrastructure is influence

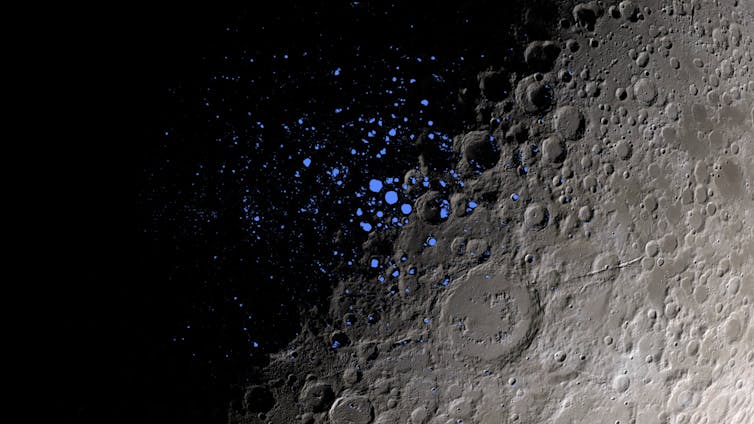

Building a nuclear reactor establishes a country’s presence in a given area. This idea is especially important for resource-rich areas such as the lunar south pole, where ice found in perpetually shadowed craters could fuel rockets and sustain lunar bases.

These sought-after regions are scientifically vital and geopolitically sensitive, as multiple countries want to build bases or conduct research there. Building infrastructure in these areas would cement a country’s ability to access the resources there and potentially exclude others from doing the same.

Critics may worry about radiation risks. Even if designed for peaceful use and contained properly, reactors introduce new environmental and operational hazards, particularly in a dangerous setting such as space. But the U.N. guidelines do outline rigorous safety protocols, and following them could potentially mitigate these concerns.

Why nuclear? Because solar has limits

The Moon has little atmosphere and experiences 14-day stretches of darkness. In some shadowed craters, where ice is likely to be found, sunlight never reaches the surface at all. These issues make solar energy unreliable, if not impossible, in some of the most critical regions.

A small lunar reactor could operate continuously for a decade or more, powering habitats, rovers, 3D printers and life-support systems. Nuclear power could be the linchpin for long-term human activity. And it’s not just about the Moon – developing this capability is essential for missions to Mars, where solar power is even more constrained.

A call for governance, not alarm

The United States has an opportunity to lead not just in technology but in governance. If it commits to sharing its plans publicly, following Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty and reaffirming a commitment to peaceful use and international participation, it will encourage other countries to do the same.

The future of the Moon won’t be determined by who plants the most flags. It will be determined by who builds what, and how. Nuclear power may be essential for that future. Building transparently and in line with international guidelines would allow countries to more safely realize that future.

A reactor on the Moon isn’t a territorial claim or a declaration of war. But it is infrastructure. And infrastructure will be how countries display power – of all kinds – in the next era of space exploration.