Share this @internewscast.com

Globally, the legitimacy of shaken baby syndrome has come under scrutiny, raising pivotal questions about its scientific foundation.

In the UK and parts of the US, medical professionals, researchers, and legal experts are questioning this diagnosis, which has historically led to family separations and criminal convictions.

However, in Australia, this critical conversation has been largely absent—until now.

:contrast(7):saturation(0.42)/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F82155644-ff50-44a8-86d0-b98873f6d2c4)

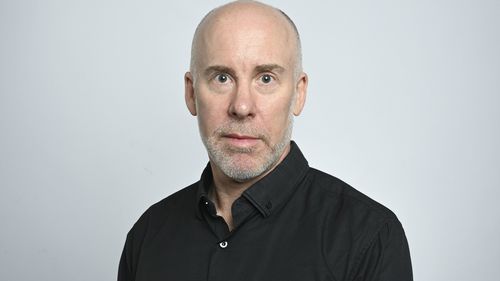

Michael Bachelard, an award-winning journalist, initially hesitated to ignite this debate.

His perspective shifted after he encountered compelling stories from Australian families, who claimed that accusations of child abuse, based on shaken baby syndrome diagnoses, were unfounded.

“It struck me as a clear instance where the medical diagnosis had leapt ahead of other crucial evidence,” Bachelard remarked to 9news.com.au.

“The injustice of it made it seem like I couldn’t ignore this.”

What is shaken baby syndrome?

Shaken baby syndrome, also known as abusive or inflicted head trauma, is a medical diagnosis based on research that dates back to the 1970s.

The original theory was that there may be a link between babies being shaken by their parents and developing subdural haematomas, or bleeding on the brain.

In the ’90s, that theory shifted into a new hypothesis; that parents were knowingly or intentionally harming babies by violently shaking them.

:contrast(22):saturation(0.78)/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F32a3e7da-7e13-4284-901e-29767fd5c23f)

This formed the basis for shaken baby syndrome, which was diagnosed based on three key clinical findings formally known as “the triad”:

- subdural haemorrhage – a specific kind of bleeding on the brain

- retinal haemorrhage – bleeding in the tissue behind the eye

- brain swelling

The diagnosis based on the triad became widely accepted and even came to be used as evidence of abuse in court cases.

‘There are questions being asked’

Child abuse is abhorrent and perpetrators should face justice.

But the science behind shaken baby syndrome and the triad is shaky and unproven, prompting a growing number of experts to question how it is diagnosed and used as evidence in court.

“We talk about the cost, as we rightly should, of child abuse,” Bachelard said.

“But there’s also a cost in getting it wrong the other way, in falsely accusing parents or carers of abuse … and that’s a cost we don’t often look at.”

He explores that cost in Diagnosing Murder, a four-part investigative podcast series from The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald.

In it, he interviews families, lawyers, doctors, and other experts to understand why shaken baby syndrome has faced scrutiny abroad but not in Australia.

Especially when it can take such a devastating toll on Australian families.

“It surprised me how the science of shaken baby syndrome, or as people now call it, abusive or inflicted head trauma, began and how it then evolved,” Bachelard said.

“And the difficulty of making any firm proof that there is an association between shaking and the medical symptoms and signs that are attributed to it.”

It’s especially concerning when you consider the number of Australian parents who have found themselves in children’s court or facing prosecution over allegations of abuse based on a shaken baby syndrome diagnosis that may not be scientifically sound.

The people who diagnose it or adhere to the current orthodoxy around it are usually well-intentioned.

But when the science behind these diagnoses isn’t accurate, the outcomes can be devastating.

”We should be questioning the science that we rely on in court, particularly when people are either having their children taken away in the children’s court, or going on and being prosecuted,” Bachelard said.

“We should be open to questions and some of those questions are difficult, but if people are being sent to prison or having their children removed wrongly on a diagnosis that doesn’t stack up scientifically, that’s terrible.

“That’s something we should all worry about.”

Kabir, Dipika, and their daughter Dua are one such family.

In 2021, the Melbourne couple rushed their daughter to hospital after she went limp at home and though she recovered, clinical findings led forensic doctors to believe she was a victim of shaken baby syndrome.

As the last person who had held her, Kabir became their prime suspect.

He was accused of child abuse and Dua was removed from her parents’ care despite Kabir’s insistence that he was innocent.

“The fact that they were prepared to sit down with me and tell me their stories also shows me how how deep they felt the injustice has been,” Bachelard said.

“And the fact that they’re prepared to risk exposure and backlash to tell their stories, you know, I was really impressed by their courage.”

:contrast(6):saturation(0.28)/https%3A%2F%2Fprod.static9.net.au%2Ffs%2F3d4e9a5d-6ebc-4b7f-83d2-59831c8909c7)

Kabir and Dipika aren’t alone.

Bachelard spoke to other parents accused of harming their children based on shaken baby syndrome diagnoses and has been contacted by more since the podcast started airing.

It’s not the response he expected.

”I expected a pretty large backlash,” Bachelard confessed.

“But a number of responses we’ve had have been, ‘this has happened to me,’ or ‘this is happening to me’.

“That response has really encouraged me to think this is worthwhile, this is something worth raising and hoping that we can prompt the discussion.”

Dissenting voices are still emerging in Australia and Bachelard is hopeful that in the near future, conversation will turn into action.

What form that action takes remains to be seen.

There have been calls for an inquiry into convictions based on shaken baby syndrome diagnoses and the questionable triad of clinical symptoms behind them.

“If we’re interested in avoiding wrongful convictions, and if we’re interested in trying to avoid the pain and suffering that these accusations can cause, then I think we do need, as a system and as a country, to take a closer look at it,” Bachelard said.

“And I do hope that this podcast helps prompt that conversation.”