Share this @internewscast.com

Kazuyo Kitada once endured an intense work schedule, toiling from 9 am to midnight on weekdays and continuing from 9 am to 5 pm over the weekends.

One night, a client reached out at 2 am. The next day, Kitada’s boss questioned her absence at the office.

“I need sleep,” she thought at the time.

During the 1990s, Kitada was employed at a Japanese IT firm where she dedicated two decades of her life. She was involved in a particularly demanding project for a challenging client, as she recounted to SBS News.

After relocating to Australia 16 years ago, Kitada noticed a work culture that prioritizes the individual over the company.

“In Australia, if someone is unwell, project timelines are adjusted,” she explains, highlighting the flexibility she now experiences compared to the rigid deadlines she faced in Japan.

“Twenty years ago, in Japan, if something happened on the first day of a family trip, you have to [go] back to the company, right?

It’s company: number one. Working: number one.

Those expectations weren’t unusual in Japan, which has long struggled with a notoriously punishing work culture marked by long hours and untenable workloads, driving a host of work-related health problems.

Death by overwork became so familiar in Japan that it has a name: karoshi.

But like many countries, Japan has seen a significant shift in attitudes towards work over the past decade, particularly among younger people and notably since the COVID-19 pandemic.

The issue was thrust back into the spotlight in October with the appointment of a new prime minister, whose personal attitude to work has fuelled controversy at home and abroad.

A leader who will ‘work, work, work, work, work’

While the extreme work culture of decades past has been on its way out for some time, overwork remains a major social flashpoint.

That’s why it sparked such debate when Japan’s new leader, conservative Sanae Takaichi, made a personal commitment to abandon work-life balance, vowing to “work, work, work, work, work” and encouraging her party’s members to do the same.

She made international headlines again in November last year, when she called a 3am meeting with aides, claiming she sleeps as little as two to four hours a night.

It stirred concerns that she is modelling a work ethic that many Japanese people are striving to move away from.

Japan’s National Defense Counsel for Victims of Karoshi said her comments “could force workers, including government employees, to overwork and work long hours and could revive an outdated mentality”.

It also drew backlash from labour unions and some members of parliament.

Yoshihiko Noda, a former prime minister and leader of the main opposition party, called the 3am meeting “crazy” in an interview with the New York Times.

“It’s a very sad attitude for the top leader of the country to show,” he said.

Takaichi’s “work, work, work” remark earned the title of Japan’s 2025 buzzword of the year, awarded by publishing house Jiyū Kokumin Sha, and sparked further backlash from the families of karoshi victims.

At the award ceremony, Takaichi emphasised that she did not intend to suggest that long working hours are a virtue, nor to encourage them among the public.

Still, Hiroshi Ono, a professor of human resources at Tokyo’s Hitotsubashi University, tells SBS News the prime minister’s original messaging sent the “wrong signal”.

“That’s exactly what we’re not supposed to do,” he says.

“If that was not Takaichi [and] that was a private company, they’d be blacklisted.

Calling a meeting at three in the morning — no, you can’t do that.

In Japan, “black companies” refer to employers known for exploitative labour practices and excessive working hours. Since 2017, the government has published lists of companies that violate employment laws.

Takaichi is also looking to relax Japan’s overtime restrictions, currently capped at 45 hours a month, as employers contend with significant labour shortages and a shrinking working-age population.

That overtime cap was introduced as part of work-style reforms passed in 2019, which were intended to “correct this work culture of excessive work hours, karoshi”, Ono says.

Takaichi’s approval rating sky high

Despite her controversial remarks about work, Takaichi has received exceptionally high approval ratings — north of 70 per cent in some polls — with very strong support from younger voters.

In December, her approval stood at more than 92 per cent among voters aged 18 to 29 and 83 per cent among those aged 30 to 39, according to a joint poll by the Sankei Shimbun newspaper and Fuji News Network, a television network.

A small survey of 100 Japanese working women aged 20 to 49 last year found that more than half took Takaichi’s remarks about work positively, with many viewing it as a personal declaration of her resolve.

Another survey, conducted by the Shufu JOB Research Institute, found that respondents had “high expectations” for the new administration regarding the promotion of women’s workforce participation.

Younger generations, particularly those raising children, appeared to hold high hopes that the appointment of the first female prime minister would lead to improvements in working conditions.

Ryoko Yoshida is a 38-year-old who works in Japan’s automotive industry.

She tells SBS News that while Japan is growing out of the “work, work, work” mentality, she suspects Takaichi felt compelled to aggressively promote her own work ethic as the first woman in the role.

But Yoshida doesn’t read the prime minister’s rhetoric as a call for the working population to mirror it.

“It’s still a society where women [are] quite looked down upon,” she says.

“You can see how motivated she is as a PM. I think it worked for younger people.”

This month, Takaichi, who took on the premier role after her predecessor resigned, called a snap election for 8 February. She told reporters she wanted “the people to decide directly whether they can entrust the management of the country to me”.

Unwinding a deeply-embedded culture

In the decades following World War Two, Japan’s rapid economic rebuild entrenched a work-first culture that prioritised output, endurance and company loyalty.

“There was no upper bound to your work hours. And so literally, we had people that were working to death,” Ono says.

More than five decades since the first documented case of karoshi, Japan records thousands of compensation claims for death and illness linked to excessive work each year, according to government data, including cases involving stroke, heart disease, mental health issues and suicide.

Recognised cases of karoshi linked to heart or brain failure have declined over the past decade, according to data from Japan’s health ministry, but a record number of people applied for mental health-related compensation in 2024.

Along with cost of living pressures, stagnant wages and entrenched gender roles, Japan’s strenuous work culture is widely blamed for making it difficult for young people to raise families, exacerbating the country’s perennially low birthrate.

In a bid to remedy that, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government introduced a flexible work system in April that gives employees the option to work four days a week while maintaining the same total working hours over a four-week period.

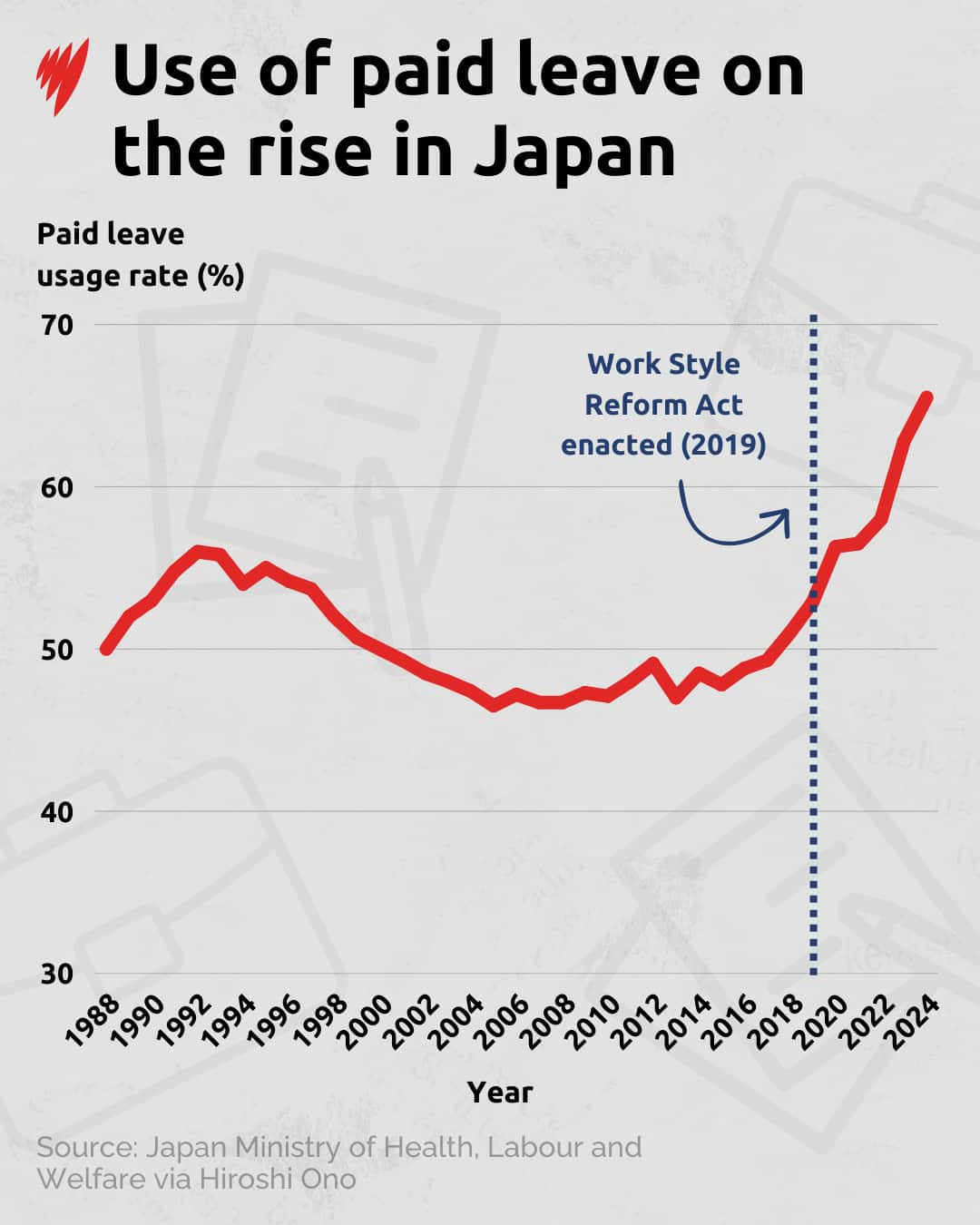

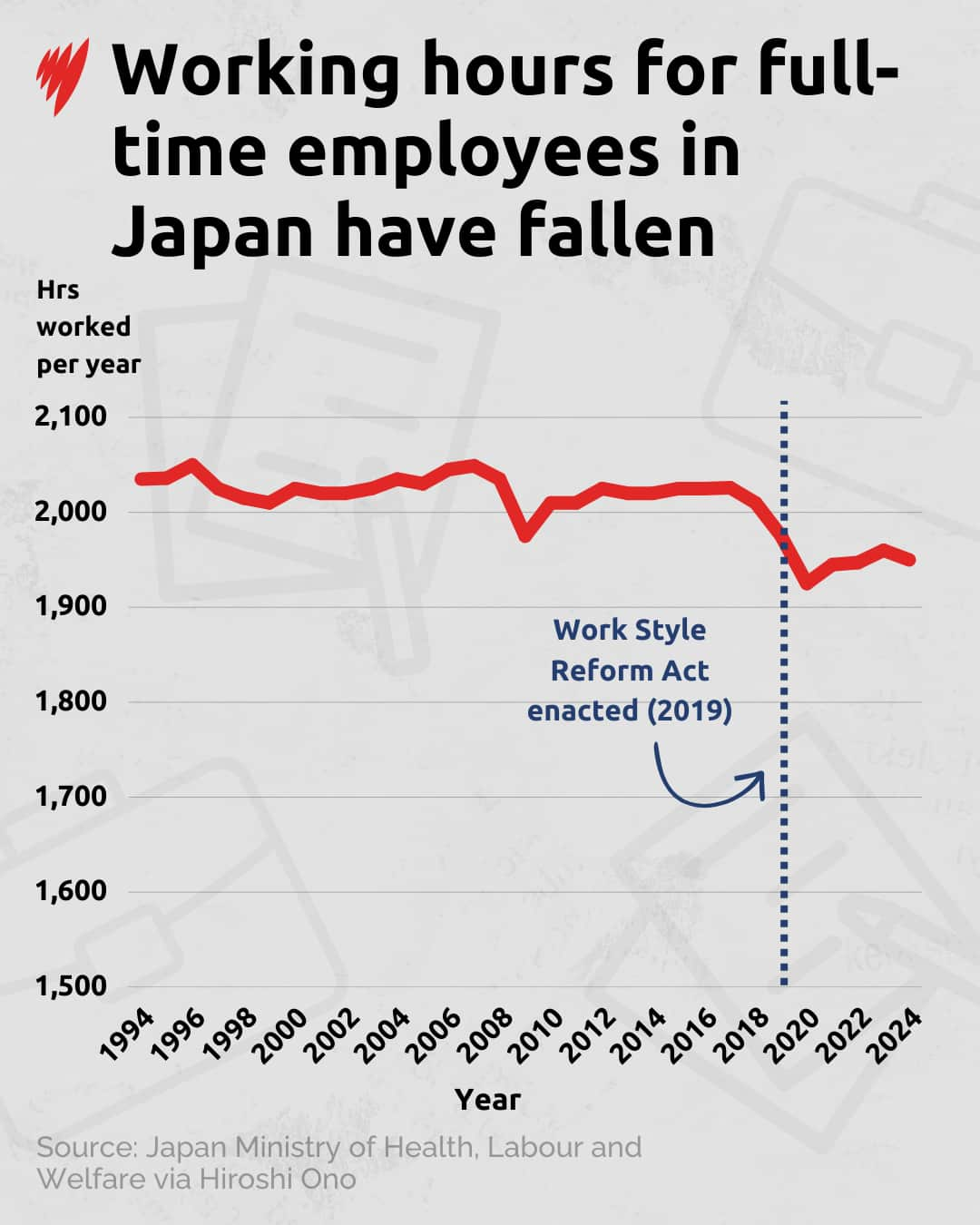

Government figures show that working hours for full-time employees declined sharply in 2019, the year that work reforms were legislated, while uptake of paid leave started to rise.

“The work-style reform act of 2019 seems to have had some impact in improving the quality of life and quality of work in Japan,” Ono says.

Full-time employees in Japan receive a legal minimum of 10 to 20 days of annual leave, depending on length of service. The 2019 reforms stipulated that employers ensure workers take at least five days of paid leave a year.

A generational shift

Ono, who is in his 50s, says his generation “didn’t ask questions” and stuck to the status quo when it came to work.

“There is definitely a significant generational divide,” he says. “Younger people these days definitely value their personal time, and they’re very much against this long-working-hour culture.”

Similarly, Kitada, 57, who now works as a producer for SBS Japanese, says young people in Japan have the courage to “speak up more than my era”.

Reflecting on how she used to work, she says it’s “really crazy” to think about.

“But at that time, it’s normal, because everybody worked the same way.”

Yoshida, a millennial working in supply chain management, says her work hours are pretty flexible, and she’s rarely expected to do overtime.

She believes younger generations are more broadly aware of their entitlements and prioritise work-life balance.

“I think younger people are not afraid to speak up to their bosses, and they don’t mind being judged for [it],” she says.

This story was produced in collaboration with SBS Japanese, with additional reporting from Kate Onomichi.

Readers seeking crisis support can contact Lifeline on 13 11 14, the Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467 and Kids Helpline on 1800 55 1800 (for young people aged up to 25).

More information and support with mental health is available at beyondblue.org.au and on 1300 22 4636.

Embrace Multicultural Mental Health supports people from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds.

For the latest from SBS News, download our app and subscribe to our newsletter.