Share this @internewscast.com

John Edwards was never content to be one of those reporters comfortably stationed behind a desk in Fleet Street, glued to a computer screen.

For nearly six decades, he found himself in the thick of the action, capturing events with precision in his reliable notebook—a real notebook, not a smartphone or any other modern gadget.

His career was akin to an immersive journey through history’s most pivotal moments. From the fiery struggle of the American civil rights movement and the grim reality of the Vietnam War, to the exhilarating race to land the first human on the moon, the meteoric rise of The Beatles, and the political ascent of Margaret Thatcher.

Edwards had a front-row seat at virtually every major global event from the early 1960s all the way into the 2000s.

His passing last Saturday, just shy of his 92nd birthday, marks the end of an era for one of the most distinguished post-war popular newspaper writers.

Edwards’ reports for the Daily Mail, spanning the UK and the world, were often raw, deeply moving, and sometimes infused with humor. Whether brief or expansive, his writing consistently cut to the core of the story. Throughout his career, covering every significant conflict from 1966 until his retirement in 2007, he consistently highlighted both the nobility and the frailty of the human spirit.

On the home front he brought a witty, sardonic eye to a country creaking under bureaucracy and political correctness. He was one of the very first reporters to examine the iniquities of the asylum system, exploding the dubious trickery he observed at first hand in chaotic immigration tribunals.

Here was a Welsh boy who left school with barely a qualification yet went on to become one of the most acclaimed and garlanded journalists of his generation.

His coverage of the fall of Saigon earned him the first of many awards. In the citation, the chairman of the judges, TV executive Bill Grundy, declared of Edwards: ‘He can move you to tears, he can rock you with laughter and – very frustrating for his fellow journalists – he can leave you wondering why the hell you didn’t think of that phrase.’

His output was prolific as he moved from one big story to another. He had no sooner stamped the snow from his boots in Iceland in 1972 after covering the great chess showdown between Russian champion Boris Spassky and the young American pretender Bobby Fischer – the match that defined the Cold War struggle between East and West – than he was boarding a US Marines helicopter in the steamy jungles of South-East Asia. (Incidentally, the Spassky/Fischer face-off was a source of a famous Edwards scoop – revealing that President Richard Nixon’s White House had an open line to the switchboard of the Reykjavik venue.)

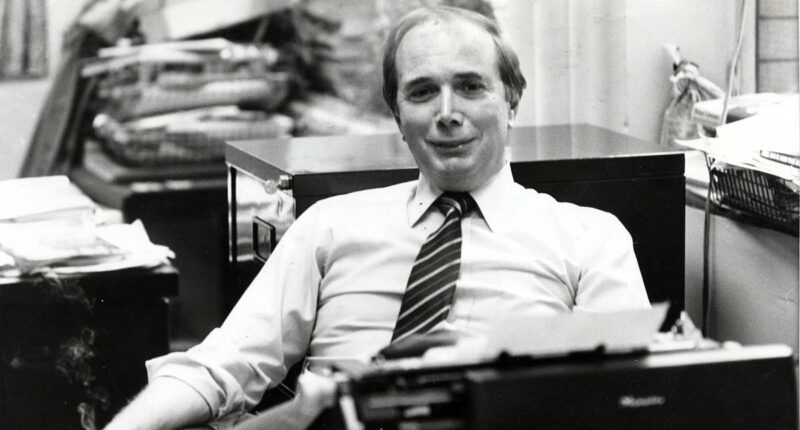

John Edwards jetting off on another adventure. ‘His despatches for the Daily Mail from every corner of Britain and the globe were often raw, frequently moving and sometimes funny,’ writes Richard Kay

‘His output was prolific as he moved from one big story to another.’ Pictured: The wordsmith at his typewriter

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, he shared his motel room in the Florida Keys with a US navy pilot who slept in his flying suit. The aviator didn’t give much chance for his – or John’s survival – in those dark days of October 1962 when the world stood on the brink of nuclear Armageddon.

He spent days chasing Marilyn Monroe in California’s High Sierra, grabbing an impromptu interview in a dusty street.

Not long afterwards he was in Westwood Memorial Cemetery, Los Angeles, reporting her funeral. ‘What a girl,’ he recalled years later. His pursuit of Frank Sinatra was less successful – but more of that later.

In many ways he was a master storyteller and he might have turned to literature, like his great friend and former Mail colleague Keith Waterhouse, but he preferred the immediacy of fact not fiction.

He met six American Presidents – handshakes with John F Kennedy in Mussel Shoals, Tennessee, who told him to say hello to England, travelled with the peanut farmer Jimmy Carter on his sweep to victory in 1976 and in Ireland in 1984 shared a pint of stout with Ronald Reagan.

If America defined Edwards’ early career, Ireland was his favourite destination. It was where he first worked as a teenager and, over the decades, would return again and again. His coverage of the Ulster hunger strikes and the hypocrisy of the IRA, who allowed their prisoners to starve to death, was exceptional.

He had no fear venturing into a Republican drinking club in West Belfast or a shebeen in South Armagh, telling this reporter: ‘Don’t worry, I’m a Celt like them.’

He was equally at home reporting on the eccentricities of the Emerald Isle, like the moving statue of the Virgin Mary in Ballinspittle, Co Cork. His amusing reports helped turn the place into a tourist attraction.

And in Newbridge, Co Kildare, Edwards’ humorous accounts of the hopeless hunt for stolen racehorse Shergar catapulted a local police detective into a trilby wearing version of Peter Sellers’ hapless Clouseau. John, of course, dubbed him O’Clouseau!

John Edwards might never have made it as a journalist but for a chance encounter in Dublin where, as a teenager, he had gone to watch an Ireland versus Wales rugby match.

Years later, he wrote how he cashed in his return ticket to buy some food. ‘I hadn’t the faintest idea what to do next,’ he said. ‘By luck I met a guy who was on newspapers and who introduced me to the editor of the Evening Herald in Dublin and I got the job.’

Born in Llanelli in 1933, he was the only son of a union official and a nurse. To his abiding gratitude, his parents moved to Haverfordwest in west Wales, which – for the rest of his life – became his home from home.

It was at the local grammar school, where he was a decent cricketer, that Edwards met Iris, the sweetheart who was to become his wife but who was to pre-decease him.

After stints on the West Wales Guardian and the Liverpool Echo, Edwards decided to abruptly change career. It was the late 1950s and a new phenomenon was sweeping the country – rock and roll. John went into public relations, helping to promote this exciting new sound.

Among those bidding for fame was a young skiffle star called Tommy Steele. Edwards, a couple of years Steele’s junior, went to work for him, hanging out in the fashionable Soho coffee bars such as the 2i’s, in Old Compton Street.

Edwards reporting at the scene of a public flogging at the Faisalbad Cricket Stadium, Pakistan

‘Here was a Welsh boy who left school with barely a qualification yet went on to become one of the most acclaimed and garlanded journalists of his generation.’ Pictured: The Daily Mail journalist riding in a Harriers T4A

But he itched to get back into the news business and pop’s loss was journalism’s gain.

He joined the staff of the Daily Mirror and in 1960 was sent by the newspaper to join its team of US correspondents based in New York. It was the start of a long love affair with America. He reported Martin Luther King’s ‘I have a dream’ speech and cowered with Dr King in a small church under a firebomb attack from the white racists of the Ku Klux Klan.

They couldn’t leave till the National Guard arrived and the church had been reduced to embers. Edwards was in Memphis when King was shot dead.

The datelines came thick and fast. He was in Israel for the Six-Day War and back in America for the Apollo space shots.

He was reporting from Mission Control Houston when Commander Jim Lovell of Apollo 13 famously radioed: ‘Houston, we’ve had a problem.’

Later he moved to the Daily Sketch, where he wrote a gossip column about people in the news.

From there he joined the new ‘compact’ Daily Mail under the legendary editorship of David English. It was to turbocharge his career.

His first piece appeared on May 6, 1971. It was about bingo and above the headline it read: ‘John Edwards, introducing yet another big name to Mail readers.’

English, who was masterminding a new kind of popular paper, sent his star writer back to New York where he wanted him to study the style of the so-called ‘new journalism’, personified by the columnist Jimmy Breslin.

Edwards perfected a unique, pitter-patter style, where every word counted and which – as much as anything – summed up the mood of an event.

It was to define the way Edwards wrote. His thrilling reports won countless admirers. In 1976 he won both Reporter of the Year and the What the Papers Say Journalist of the Year.

Both were for his Vietnam coverage. In April 1975, as everyone fled the advancing Viet Cong, Edwards stayed to witness the last firefight in a war which had humiliated the mighty USA.

Although John was by no means addicted to danger, he was drawn to it and admitted experiencing the rush generated by the camaraderie, the fear, the excitement and the anger of conflict. He was still reporting wars in the former Yugoslavia in the 1990s. After Saigon, he ventured to the dark heart of Africa and a terrifying confrontation with the white-suited dictator Jean-Bedel Bokassa, self-styled emperor of the Central African Empire. Bokassa was reputed to be a cannibal who liked nothing more than to kill, roast and eat his opponents. He talked of trading diamonds for bombs. Edwards, desperate to get out alive, promised to help.

Not long afterwards he was granted an audience with Master Sgt Samuel K. Doe, who hacked his way to the leadership of Liberia. He invited Edwards to watch the execution of his foes: nine members of the previous ruling clan were tied to posts and shot.

On a visit to Ugandan capital Kampala, dictator Idi Amin told Edwards if he had any complaints he should come to him. He was as good as his word, sending a box of soap together with a note from the presidential palace when Edwards let him know that the Hotel International had run out. In Pakistan, General Zia, who seized power in a coup in 1977, invited Edwards to see the ‘reforms’ he was carrying out.

Edwards at the Metropolitan Police firearms training school, Epping Forest

John found himself in a cricket ground in Faisalabad, where a man was flogged to death in front of a crowd of 40,000 on the very spot where Geoffrey Boycott had scored a century not long before.

The assignments and the scoops came thick and fast: smoking cigarettes with the surgeon who saved Pope John Paul II after a Turkish gunman put four bullets in him; giving a lift to Mother Teresa after the living saint’s taxi broke down and she was running late for a meeting with the Queen; flying pillion in a Harrier jump jet training to take on the Argentine air force in the Falklands War.

In 1980, he resorted to subterfuge, passing himself off as the wedding cake maker to infiltrate the marriage ceremony of murderous Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier in Port-au-Prince, Haiti.

Later still he began a column, The Way It Is, bringing the same vivid style to domestic events. When it was all over, it was back to Wales and his beloved rugby.

He knew all the greats. Once walking to the Millennium Stadium in Cardiff for a match with England he fell into step with the distinguished, long-retired ex-player Phil Bennett. Wales were not favourites. ‘Got your boots?’ Edwards asked. Quick as a flash, Bennett replied: ‘Got yours boyo, you’d get on.’

Last night Paul Dacre, Editor in Chief of Associated Newspapers and Edwards’ former boss said: ‘John was one of the last great writer-reporters from the halcyon days of Fleet Street when print, not the web, ruled journalism and globetrotting firemen like him were its stars.

‘For John, the words which told a story were as important as the facts. Both were sacred. But for him, Heaven was a perfect intro.’

Mr Dacre added: ‘He was a brilliant popular newspaper journalist – at a time when such papers were read by tens of millions – because of his ability to make huge, often complex events highly readable to the man in the street.

‘He did so in his unique style often focusing on the oblique detail, talking to obscure bit players behind the scenes and painting, in his spare, muscular prose with its staccato rhythms, a picture that captured the mood of an event far more powerfully than conventional news reports.’

He was, Mr Dacre added, ‘a man who effervesced with an inexhaustible creative energy and effortless wit’.

So what about Sinatra? The legendary singer asked Edwards to meet him at The Savoy hotel and there Edwards waited and was ignored all day.

When Sinatra later appeared at the Albert Hall, Edwards had a front row seat.

Remembering his humiliation, Edwards’ devastating piece read: ‘Sinatra came on to the stage wearing someone else’s hair…’