Share this @internewscast.com

Miccosukee leaders had already condemned the makeshift compound of trailers and tents that rose out of the swamp in a matter of days.

TALLAHASSEE, Fla. — The Miccosukee Tribe of Indians of Florida is looking to become a part of a federal lawsuit with the aim of stopping the development and operation of a new immigration detention center in the Everglades, lands that tribal members hold as their sacred ancestral homelands.

Miccosukee leaders had previously criticized the temporary compound of trailers and tents that appeared in the swamp within days. However, by filing a motion on Monday to intervene in the case initially brought by environmental organizations, the tribe is demonstrating a heightened level of opposition, particularly as a significant political contributor in the state.

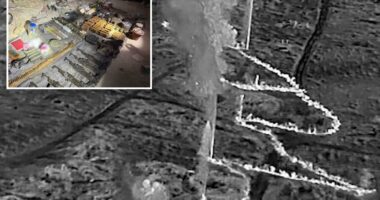

Under the administration of Republican Gov. Ron DeSantis, the state quickly established the facility, nicknamed “Alligator Alcatraz” by state officials, on an isolated, county-owned airstrip within the Big Cypress National Preserve, approximately 45 miles (72 kilometers) west of downtown Miami.

The Miccosukee have lived on and cared for the lands of Big Cypress “since time immemorial,” the filing reads, noting that the tribe played an integral role in pushing for the creation of the national preserve, the country’s first.

“The area now known as the Preserve is a core piece of the Tribe’s homeland. Today, all of the Tribe’s active ceremonial sites and a significant majority of the Tribe’s traditional villages (sometimes known as “clan camps”) are within the Preserve,” the filing reads.

To DeSantis and other state officials, locating the facility in the rugged and remote Everglades is meant as a deterrent, a national model for how to get immigrants to “self-deport.” The Republican Party of Florida has taken to fundraising off the detention center, selling branded T-shirts and beer koozies emblazoned with the facility’s name. Officials have touted the harshness of the area, saying there’s “not much” there other than the wildlife who call it home.

In fact, the Miccosukee have lived on those lands for centuries, the tribe’s attorneys wrote in their motion, which notes that there are 10 tribal villages within a three-mile (4.8-kilometer) radius of the detention center, one of which is approximately 1,000 feet (304 meters) from the facility.

The preserve is a place where tribal members continue to hunt, trap and fish, as well as catch the school bus, hold sacred rituals and bury their loved ones.

“The facility’s proximity to the Tribe’s villages, sacred and ceremonial sites, traditional hunting grounds, and other lands protected by the Tribe raises significant concerns about environmental degradation and potential impacts,” the filing reads.

The lawsuit originally filed by the Friends of the Everglades and the Center for Biological Diversity seeks to halt the project until it undergoes a stringent environmental review as required by federal and state law. There is also supposed to be a chance for public comment, the plaintiffs argue.

As of Tuesday afternoon, the judge in the case had not acted on the groups’ requests for a temporary restraining order and preliminary injunction to stop activity at the site.

The state raced to build the facility at the isolated airfield before the first detainees arrived on July 3. Streams of trucks carrying supplies like portable toilets, asphalt and construction materials drove into the facility’s gates around the clock as workers assembled a network of massive tents that officials said could ultimately house 5,000 detainees.

What had been an internationally designated “dark sky” park far away from urban development is now blasted by lights so powerful, the glow can be see from 15 miles (24.1 kilometers) away, the environmental groups said.

The area’s hunting and fishing stocks could be so significantly impacted, attorneys argue the tribe’s traditional rights — guaranteed by federal and state law — could be “rendered meaningless.”

Copyright 2025 Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed.