Share this @internewscast.com

In the heart of Boston, David Arsenault experiences a sense of reverence each time he selects a weathered, leather-bound tome from the Boston Athenaeum’s extensive collection. To him, it’s akin to holding a treasured artifact within a museum.

Spanning the library’s seemingly infinite labyrinth of reading rooms and stacks are approximately half a million books, many of which were printed long before his ancestors walked the Earth. Nestled among the pages are tattered Charles Dickens novels, biographies from the Civil War era, and local genealogies, each with its own story and vitality.

“It feels almost sacrilegious to think about taking these books out of the building; they seem so special,” Arsenault remarked, frequenting the institution beside Boston Common several times weekly. “It’s like being in a museum, but one where you’re not just an observer. Here, you become part of the experience.”

Boasting over two centuries of history, this venerable institution is among roughly 20 surviving member-supported private libraries in the United States that trace their origins to the 18th and 19th centuries. Known as athenaeums, derived from the Greek for “temple of Athena,” these establishments predate the conventional public libraries familiar today. They were founded by a diverse group—including merchants, doctors, writers, lawyers, and ministers—seeking to foster not only reading, which was once an expensive and rare pursuit, but also a space for cultural exploration and intellectual discourse.

These athenaeums remain vibrant hubs within their communities.

Visitors come together to engage in games, delve into discussions about James Joyce, or conduct genealogical research. Some come to admire significant historical treasures, such as the most extensive collection of books from George Washington’s personal library at Mount Vernon, housed within the Boston Athenaeum.

In addition to conservation work, institutions acquire and uplift the work of more modern creatives who may have been overlooked. The Boston Athenaeum recently co-debuted an exhibit by painter Allan Rohan Crite, who died in 2007 and used his canvas to depict the joy of Black life in the city.

One thing binds all athenaeums together: books and people who love them.

“The whole institution is built around housing the books,” said Matt Burriesci, executive director of Providence Athenaeum in Rhode Island. “The people who come to this institution really appreciate just holding a book in their hands and reading it the old-fashioned way.”

Book lover’s dream

Built to mimic an imposing Greek temple, staffers at the Providence Athenaeum often talk about the joy of watching people enter for the first time.

Visitors must climb a series of cold, granite steps. Only then are they met with a thick wooden door that ushers them into a warm world filled with cozy reading nooks, hidden desks to leave secret messages to fellow patrons, and almost every square inch bursting with books.

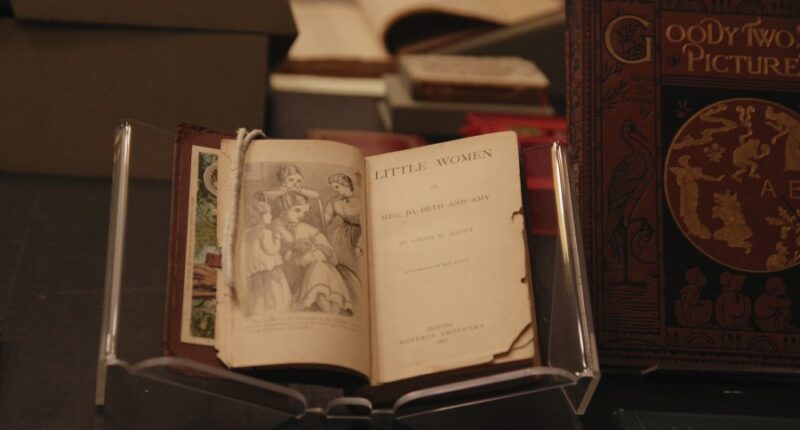

“It’s the actual time capsule of people’s reading habits over 200 years,” Burriesci said, while pointing to a first-edition of Little Women, where the pages and spine proudly showcase years of being well read.

Many athenaeums are designed to pay tribute to Greek influence and their namesake, the goddess of wisdom. In Boston, a city once dubbed “the Athens of America,” visitors to the athenaeum are greeted by a nearly 7-foot-tall (2.1-meter-tall) bronze statue of Athena Giustiniani.

The building is as much an art museum as it is a library.

“So many libraries were built to be functional — this library was built to inspire,” said John Buchtel, the Boston Athenaeum’s curator of rare books and head of special collections.

The 12-level building includes five gallery floors where ornate busts of writers and historical figures decorate reading rooms with wooden tables overlooked by book-lined pathways reachable by spiral and hidden staircases.

Natural light shines in from large windows where guests can look down to see one of Boston’s most historic cemeteries where figures like Paul Revere, Samuel Adams, and John Hancock are buried.

“We’re able to leave many of these things out for people to peruse, and I think people can often get curious about something and just follow their curiosity into things that they didn’t even know that they were going to be fascinated by,” said Boston Athenaeum executive director Leah Rosovsky.

A safe haven

When athenaeums were founded, they were exclusive spaces that only people with education and money could access.

Some are now free. Most are open to the public for day passes and tours. Memberships to the Boston Athenaeum can range from $17 to $42 a month per person, depending on whether the patron is under 40 or is sharing the membership with family members.

Charlie Grantham, a wedding photographer and aspiring novelist, said she first visited during one of the institution’s annual community days, where the public can explore for free. She said she was surprised by how accessible it was and describes the space as “Boston’s best kept secret — an oasis in the middle of the city.”

“It’s just so peaceful. Even if I’m still working… doing things I’m stressed out about at home, when I’m here, there’s like a stillness about it and things feel more manageable, things feel enjoyable here,” she said.

Some people visit every day to work remotely, read or socialize, said Salem Athenaeum executive director Jean Marie Procious.

“We do have a loneliness crisis,” she said. “And we want to encourage people to come and see us as a space to meet up with others and a safe environment that you’re not expected to buy a drink or buy a meal.”