Share this @internewscast.com

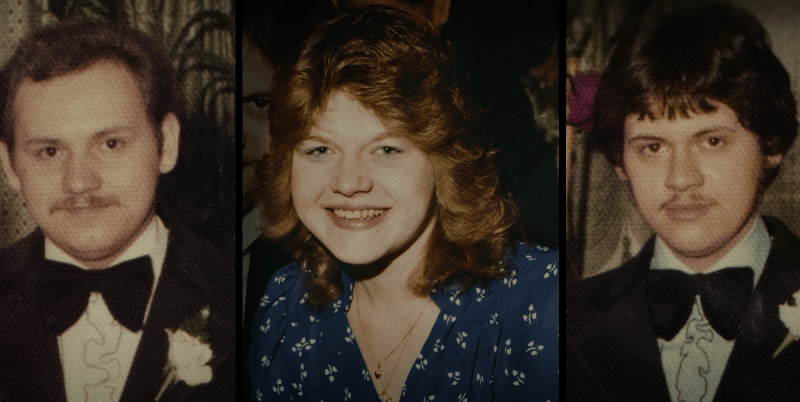

WHEN 27-year-old Adam Janus woke up for work feeling under the weather, he did what many of us would naturally do and popped a couple of painkillers.

Hours later he was dead, having collapsed at his home in Chicago from a suspected heart attack.

It left his devastated family baffled, but there was more heartbreak in store.

That afternoon, Adam’s brother Stanley, who was 25 at the time, and his wife Theresa, aged 20, visited his home. Both feeling ill, they reached for the bottle of Extra Strength Tylenol painkillers that Adam had used earlier that day.

Shortly afterwards, horror unfolded before the family’s eyes as the newlywed couple collapsed, foaming at the mouth.

Within hours they too had died – with the finger of blame eventually pointed at the Tylenol.

Blood samples from the victims, including a local 12-year-old girl who died under similar conditions on the same September day in 1982, showed signs of cyanide poisoning. Authorities concluded that the pills had been tampered with.

Despite investigations, the person responsible was never caught. A new Netflix documentary titled Cold Case: The Tylenol murders delves into the disturbing theories surrounding these unresolved deaths.

Speaking in the show, Adam and Stanley’s brother Joseph Janus recalls the harrowing moment Stanley collapsed.

“We were sitting on the couch. Stanley stood up and said a couple of words. And then he fell down,” he says.

“White foam was coming out of his mouth, and he started shaking. His eyes turned white.”

For the second time that day, emergency service Chuck Kramer was called to the address.

He could immediately tell that Stanley was dying – and as his wife screamed for help, she too suddenly keeled over.

Chuck recalls: “I knelt down and I turned her over, and as soon as I did, I looked into her eyes and they were fixed.

“Her pupils were dilated and her breathing was rapid and shallow, the same as [Adam] earlier and her husband.”

Recounting the bizarre cases back at the office, Chuck’s colleague told him about Mary Kellerman, a 12-year-old who had also died that day after taking Tylenol for cold symptoms.

Moments after taking the pills her parents heard a loud thud in the bathroom – and Mary never got up.

Dr Thomas Kim of Northwest Community Hospital was the first to indicate cyanide poisoning as a possible cause of death.

He says in the film: “I was pacing in the room looking through the pharmacological books, and that’s when I thought about cyanide poison, like in the spy movies when someone would bite on the tablet and they’re instantly dead.”

I was pacing in the room looking through the pharmacological books, and that’s when I thought about cyanide poison, like in the spy movies when someone would bite on the tablet and they’re instantly dead

Dr Thomas Kim

Blood samples confirmed Dr Kim’s worst fears, and the following day the medical examiner’s office scrambled to put out a press conference to warn the public.

That warning came too late for 27-year-old Mary Reiner, who had just given birth to her fourth child.

Her then eight-year-old daughter Michelle Ronsen returned home from school to find her mother gravely unwell.

Michelle says in the documentary: “Her breathing was erratic – It was hard.

“I still remember the breathing and her eyes and how scared she looked.

“And the next I know is I’m watching my mum go out on a stretcher. I didn’t realise she had died.”

Mary McFarland, 31, became the sixth victim, after taking the capsules when she fell ill at work.

The growing death toll sent detectives scrambling to get to the bottom of the case.

Meanwhile poison control centres were inundated with calls from concerned people and volunteers went from door-to-door warning people about taking the drugs.

Superintendent Richard Brzeczek, who was among the officials handling the case, says: “The general population of the Chicago metropolitan area was about six million people.

“Six million terrified people, all wondering if the next thing I put in my mouth is going to be contaminated, and am I going to die?

“And there was terror. There was fear.”

I still remember the breathing and her eyes and how scared she looked. And the next I know is I’m watching my mum go out on a stretcher. I didn’t realise she had died

Michelle Ronsen

Investigators theorised that the capsules, which had two parts, were being pulled apart, emptied and refilled with cyanide, then put back together and placed back on the shelves.

An estimated 25-30 million bottles of Tylenol bottles were recalled, the largest in American history, while authorities launched an investigation into parent company Johnson & Johnson’s plants in Pennsylvania and Texas.

It was quickly ruled out that the poison came from the factories, and with no crime scene, investigative leads or witnesses, cops were at a standstill.

Meanwhile the death toll continued to rise.

On October 1, 1982, 35-year-old flight attendant became the seventh victim.

Her friend Jean Leavengood, who found her in her apartment, tells the documentary: “The policeman asked us [if] we tried to resuscitate her. And we said no.

“He said, ‘There’s so much cyanide on her lips that if you had tried, you might have ended up dead’.”

When CCTV emerged showing her buying a bottle of Tylenol, cops zoned in on a man in the store staring intensely at Paula as she picked up the capsules. They finally had a suspect.

Chilling warning

A week after the killings began, a sinister letter landed on the desk of the Tylenol makers, warning more people would die unless demands were met – one being a $1million transfer to a Continental Bank account.

The trail soon veered towards Robert Richardson, a Chicago man whose handwriting matched the extortionist letter, and whose face looked eerily like the one seen eyeing Paula at the store.

Police plastered his face across the country, and it emerged Richardson and his wife Nancy – who also used the names James and Leann Lewis – had fled Kansas City, where he had been charged with murder and extortion after the body of a colleague, Raymond West, was found dismembered and ‘semi-mummified’ in Mr West’s attic.

The charges were later dropped when the victim’s cause of death couldn’t be determined.

James Lewis became the prime suspect in what became one of America’s most chilling unsolved cases.

He appears in the documentary, insisting: “They make it look like I’m the world’s most horrible, dangerous person ever,” before chuckling: “I wouldn’t hurt anybody.”

But his past was anything but squeaky clean.

In 1981 Lewis was linked to credit card fraud and identity theft. A raid uncovered notebooks detailing scams and a book about poisoning.

Police issued a warrant, but Lewis and his wife had already gone on the run.

Lewis was found guilty of extortion in October 1983 and jailed for 10 years, but his lawyer argued he’d written the letter to get back at his wife’s former employer.

In it, Lewis had requested the ransom money be placed in a nonactive account belonging to his wife’s former boss, the New York Times reported at the time.

Lewis repeatedly denied that he was the killer, but police continued to question him for decades, with investigators talking to him at least 34 times from when officials re-opened the case in 2006.

Cops could never place Lewis in Chicago shortly before the murders and had trouble identifying a timeline of when Lewis wrote the letter to Johnson & Johnson.

In the documentary Lewis claims he “did not consider it an extortion letter” because “I did not actually have access to making any money from the letter”.

“I was trying to do something good but I got it all screwed up,” he adds. “It was just a piece of paper. It couldn’t hurt anyone. Maybe get a paper cut.”

Damage control

Johnson & Johnson worked hard to restore public trust, relaunching Tylenol with press conferences, flashy ads and new tamper-proof seals on every bottle.

It seemed the horror was behind them – until 1986.

In New York, 23-year-old Diane Elsroth died after taking extra-strength Tylenol laced with cyanide at her boyfriend’s home.

Two more tainted bottles were found on shelves. A killer was clearly still at large, but still, no suspect.

More troubling revelations emerged. The day before the first deaths in 1982, cops had found several opened Tylenol capsules outside a diner.

One officer who handled them later suffered painful symptoms and the capsules were meant to be sent to a state crime lab, but never made it.

Superintendent Brzeczek says: “It seems like that’s almost a forgotten issue. That could have very well been the weapons of the Tylenol murderer.”

Roger Arnold became another suspect in 1982 after ranting in a bar about poisons.

A police raid on his home turned up lab gear, gunpowder and a manual on making poisons, but no cyanide.

Paranoid and humiliated, Arnold snapped and shot dead 46-year-old John Stanisha, wrongly believing he’d tipped off the cops.

He was convicted of murder in 1984 and served 15 years of his 30-year sentence. He died in 2008, and two years later his body was exhumed for DNA testing in an attempt to link him to the Tylenol case – but he wasn’t a match either.

Michelle Rosen, whose mum died in the poisonings, remains deeply suspicious of Johnson & Johnson.

With 22 million bottles destroyed by the company, only a tiny sample was ever tested. Michelle says: “I think we would’ve found a lot more poisoned capsules in those bottles.”

Initially the firm claimed there was no cyanide on site. But Nicholas Mennuti, who investigated the case, says: “They were using it at McNeil, but it wasn’t locked up and almost anyone could walk into the room where they were keeping it.”

Author Gardiner Harris adds: “Certainly from a corporate perspective, there was no deliberate effort on the part of Johnson & Johnson to distribute contaminated Tylenol.

“But there might have been some kind of problem either at their two manufacturing facilities or anywhere along the distribution chain.”

Blasting the original probe, he adds: “The investigation was problematic from the start. Would you let a suspect perform their own investigation? No.”

The investigation was problematic from the start. Would you let a suspect perform their own investigation? No.

Gardiner Harris

Even Lewis pointed the finger at Johnson & Johnson, claiming: “Only a mass murderer would want to destroy all the evidence.

“You’re behaving in a way that seems to implicate you in the murders themselves.”

In 1983, families of the Chicago victims dragged Johnson & Johnson to court claiming it knew its Tylenol bottles were laced with poison.

The company settled the lawsuits for a reported $50million, but never admitted any wrongdoing.

After the suit, the firm said: “Though there is no way we could have anticipated a criminal tampering with our product or prevented it, we wanted to do something for the families and finally get this tragic event behind us.”

Lewis died in 2023, and Richard Brzeczek is one of the few law enforcement officers who believe he wasn’t guilty of the poisonings.

“James Lewis is an as***le, but he is not the Tylenol killer,” he says. “Why the FBI expended resources that they did in trying to tie him to the Tylenol murders, I do not know.”

Cold Case: The Tylenol Murders drops on Netflix on Monday 26 May.