Share this @internewscast.com

Recently, Northern Arizona experienced its first fatality linked to pneumonic plague since 2007. Additionally, early last year, Oregon encountered its initial case of bubonic plague after several years, with the last one occurring in 2015.

Person-to-person spread of the plague hasn’t been seen in more than 100 years in the U.S., but cases occasionally pop up. So what causes them?

Today’s plague outbreaks in the U.S. differ somewhat from those that ravaged medieval Europe. During a brief span between 1347 and 1352, the plague claimed the lives of at least 25 million people across Europe.

The introduction of the bubonic plague to Europe is attributed to rats on a ship arriving from Crimea and Asia, which docked in Sicily. After European rodents succumbed to the disease, fleas sought out human hosts who were not resistant to the plague.

To combat the spread, those infected or suspected of carrying the plague were isolated, a practice reminiscent of the guidelines followed during the COVID pandemic. The development of a vaccine in the late 1800s, along with improved sanitation, enhanced health practices, and modern antibiotics, has effectively curbed the spread when outbreaks occur.

On average, the U.S. reports about seven plague cases each year, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The World Health Organization notes that the majority of human cases over the last three decades have occurred in Africa.

In the U.S., cases mostly arise in the Western states, with New Mexico and Arizona reporting the highest numbers. The illness has also been detected in regions like southern Oregon, far western Nevada, and California.

U.S. cases are, most often, bubonic.

There are three main forms of the plague: bubonic (the most common during Europe’s Black Death), septicemic, and pneumonic. Generally speaking, plague is brought on by the Yersinia pestis bacterium, with humans and mammals being affected.

The three types of plague present with different symptoms and are caused by different things.

Bubonic plague is caused by the bites of fleas that are mostly found on rodents. Symptoms of bubonic plague, the Cleveland Clinic explains, include a sudden high fever; chills; headaches; pain in the abdomen, arms, and legs; and large, swollen lymph nodes that can leak pus. While the bacteria will multiply in the lymph node where it entered the body, it’s capable of spreading to other parts of the body if not treated with antibiotics.

Septicemic plague has similar symptoms to bubonic plague, including fever, chills, extreme weakness, pain in the abdomen, shock, and the possibility of bleeding into the skin and other organs, the CDC explains. This form of plague can develop from untreated bubonic plague as well as from the handling of infected animals.

Should a person with bubonic or septicemic plague go without treatment, and the bacteria reach their lungs, they can develop pneumonic plague. A person can also get pneumonic plague from breathing in “droplets coughed out by another person or animal with pneumonic plague,” according to the CDC. Like other forms of plague, a person infected with pneumonic plague may develop a fever, headache, weakness, and pneumonia, with the latter developing “rapidly.”

While bubonic and septicemic plague may take a few days to set in, the incubation period for pneumonic plague may be just over a day, the CDC reports. It’s the only form that can be spread person-to-person, and it is considered the most serious form of the disease.

Between 2020 and 2023, the CDC reported 15 human plague cases were reported. Of those, three died. As the Cleveland Clinic explains, plague has to be treated with antibiotics as quickly as possible — taking antibiotics within 24 hours of symptoms gives you “the best chance of getting better.” You could begin feeling better within a week or two, as long as you receive treatment, according to health experts.

Regardless of the type of plague, about 90% survive with quick treatment. Untreated, “plague is nearly always fatal,” the Cleveland Clinic said.

Health officials have not said how the Arizona resident who died earlier this year of the pneumonic plague became infected. Oregon’s case of bubonic plague last year was believed to be brought on by a pet cat. In recent years, Colorado has reported a cat testing positive for septicemic plague and a cat, two prairie dog colonies, and a squirrel testing positive for bubonic plague.

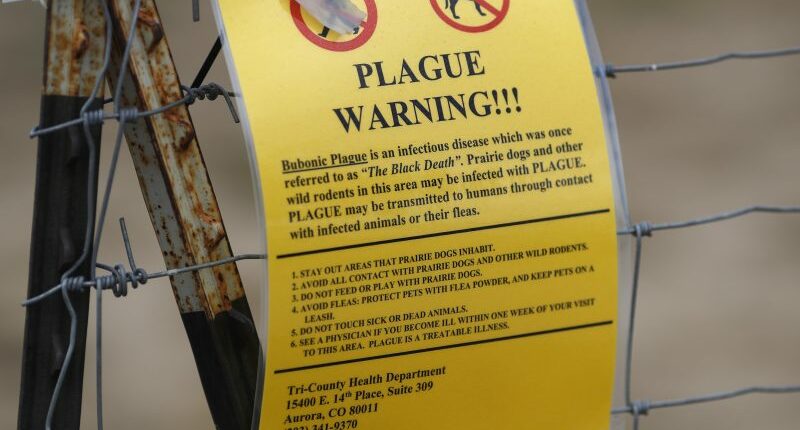

Infected fleas are largely to blame for plague cases that occur in the U.S. today, but the handling of infected animals – like cats, rabbits, rats, mice, and squirrels, according to New York’s Department of Health – has also been known to lead to the plague.

To avoid getting the plague, it’s recommended that you take steps to avoid flea bites. That includes wearing bug spray with DEET and clearing up spaces outside where the wild animals fleas love may live. It’s also important to speak with your veterinarian about preventing fleas on your pets. Your pets should also not be allowed to roam outdoors freely if you live in an area prone to the plague.