Share this @internewscast.com

Food banks and pantries, already grappling with cuts from federal programs earlier this year, are now preparing for an overwhelming influx of individuals in need. This surge is anticipated as federal food aid to low-income households stands on the brink of suspension due to the ongoing government shutdown.

The demand is already evident. Over the weekend, the food pantry at Central Christian Church in downtown Indianapolis faced an unexpected challenge as they worked to serve nearly double the usual number of visitors in just one day.

Volunteer Beth White highlighted the situation, noting, “There’s been a noticeable increase in demand, largely due to the downturn in the economy. With potential disruptions in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) funding, the situation is likely to worsen for many families.”

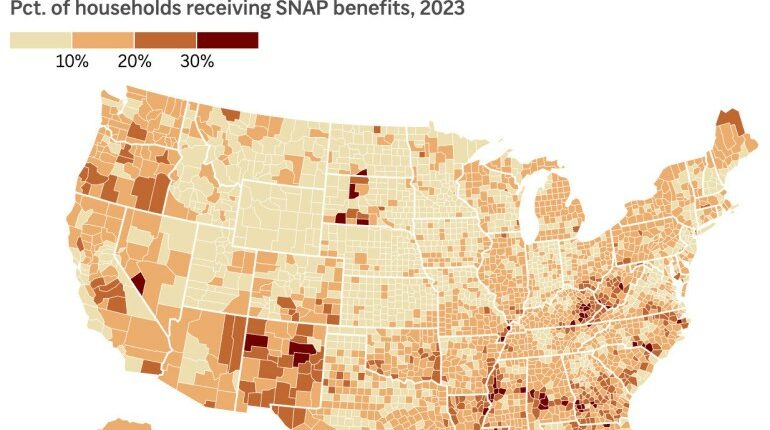

This concern resonates with food charities nationwide, as states anticipate the impact of reduced SNAP benefits on low-income families. The SNAP program, pivotal in aiding 40 million Americans—approximately one in eight people—enables them to purchase groceries using debit cards loaded by the federal government each month.

This support, however, is set to stall at the beginning of next month. The Trump administration announced on Friday that it would not utilize an available $5 billion contingency fund to continue food aid in November during the shutdown. Furthermore, the administration has clarified that states covering the cost of food assistance in the interim will not receive reimbursement.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture summed up the dire situation, stating, “Bottom line, the well has run dry. At this time, there will be no benefits issued on November 1.”

It’s the latest in a string of hardships placed on charitable food services, which are intended to help take up the slack for any shortcomings in federal food assistance — not replace government help altogether.

Charities have seen growing demand since the COVID-19 pandemic and the following inflation spike, and they took a hit earlier this year when the Trump administration ended programs that had provided more than $1 billion for schools and food banks to fight hunger.

Food pantry visitors are worried

Reggie Gibbs, of Indianapolis, just recently started receiving SNAP benefits, which meant he didn’t have to pick up as much from Central Christian Church’s food pantry when he stopped by on Saturday. But he lives alone, he said, and worries what families with children will do.

“I’ve got to harken back to the families, man,” he said. “What do you think they’re going to go through, you know?”

Martina McCallop, of Washington, D.C., said she’s worried about how she’ll feed her kids, ages 10 and 12, and herself, when the $786 they get in monthly SNAP benefits is gone.

“I have to pay my bills, my rent, and get stuff my kids need,” she said. “After that, I don’t have money for food.”

She’s concerned food pantries won’t be able to meet the sudden demand in a city with so many federal workers who aren’t being paid.

In Fairfax County, Virginia, where about 80,000 federal workers live, Food for Others executive director Deb Haynes said she doesn’t expect to run out of food entirely, largely because of donors.

“If we run short and I need to ask for help, I know I will receive it,” Haynes said.

Food banks feel the increased demand

Food pantries provide about 1 meal to every 9 provided by SNAP, according to Feeding America, a nationwide network of food banks. They get the food they distribute through donations from people, businesses and some farmers. They also get food from U.S. Department of Agriculture programs and sometimes buy food with contributions and grant funding.

“When you take SNAP away, the implications are cataclysmic,” Feeding America CEO Claire Babineaux-Fontenot said. “I assume people are assuming that somebody’s going to stop it before it gets too bad. Well, it’s already too bad. And it’s getting worse.”

Some distributors are already seeing startling low food supplies. George Matysik, executive director of Share Food Program in the Philadelphia area, said a state government budget impasse had already cut funding for his program.

“I’ve been here seven years,” Matysik said. “I’ve never seen our warehouses as empty as they are right now.”

States scramble to fill in where they can

New York Gov. Kathy Hochul said she is fast tracking $30 million in emergency food assistance funds to “help keep food pantries stocked,” and New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said her state would expedite $8 million that had been allocated for food banks.

Officials in Louisiana, Vermont and Virginia said last week they would seek to keep food aid flowing to recipients in their states, even if the federal program is stalled.

Other states aren’t in a position to offer much help, especially if they won’t be reimbursed by the federal government. Arkansas officials, for example, have been pointing recipients to find food pantries, or other charitable groups — even friends and family — for help.

——-

AP writers JoNel Aleccia in Los Angeles, Anthony Izaguirre in Albany, New York, Susan Montoya Bryan in Albuquerque, and video journalists Obed Lamy in Indianapolis and Mike Householder in Detroit contributed to this report.