Share this @internewscast.com

WASHINGTON — In June 2019, the Supreme Court dismissed the notion that federal courts could limit state legislators’ ability to create legislative boundaries primarily to reinforce their party’s dominance.

The decision, split 5-4 along ideological lines with conservative justices prevailing, affirmed that partisan gerrymandering would persist unless individual states intervened or Congress unexpectedly enacted a nationwide prohibition.

Chief Justice John Roberts, writing for the majority, noted that federal courts lacked the power to address the issue, even if it led to election outcomes that “seem unjust.”

With advancements in technology making it straightforward to meticulously design districts for partisan benefit, both Republican and Democratic states have continued this strategy.

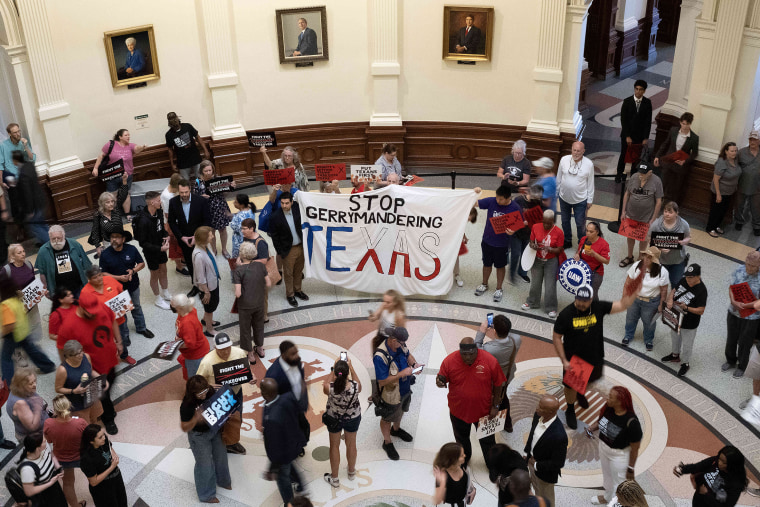

Currently, this practice is evident in Texas, where Republicans intend to redraw congressional boundaries to solidify their control in the state and protect against potential Democratic gains in the 2026 midterm elections. These elections will impact control of the House of Representatives for the concluding two years of President Donald Trump’s term.

That has prompted Democrats in California and other states to threaten countermeasures.

“This is just a very ugly race to the bottom,” explained Richard Pildes, an election law expert at New York University School of Law who has supported reform efforts. Given the closely contested nature of the House, Texas is motivated to “extract every district possible,” he stated.

The legal background of redistricting

Under the Constitution, state legislatures have the primary role of drawing legislative maps, but Congress has the specific power to intervene should it choose and set rules for how it should be done.

States are required to draw new legislative maps after the census that takes place every 10 years.

Texas and all the other states have already drawn new maps after the 2020 census. The latest saga was prompted when Gov. Greg Abbott proposed a mid-decade re-draw for overt political gain, urged on by Trump.

States are not prohibited from drawing new maps between censuses, but it is rarely done.

Texas is “bashing through norms that were keeping folks in check,” said Sophia Lin Lakin, a lawyer at the American Civil Liberties Union who works on voting rights cases.

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in the partisan gerrymandering dispute, there are some restrictions on how states draw districts.

Under the Supreme Court’s “one person, one vote” precedent, the populations of every district must be similar so the power of each individual voter is not diluted.

Another constraint, at least for now, is the landmark Voting Rights Act, a law passed 60 years ago this week to protect minority voters.

But the Supreme Court, which has a 6-3 conservative majority, has weakened that law in a series of rulings.

A ruling in 2013 gutted a key provision that required certain states with histories of race discrimination to get approval from the federal government before they change state voting laws, which included the adoption of new district maps.

Just last week, the court indicated it could further weaken the Voting Rights Act in a case involving Louisiana’s congressional districts.

The court said it would consider whether it is unconstitutional, under the 14th and 15th Amendments, for states to consider race in drawing districts intended to comply with the voting law.

A ruling along those lines would be “potentially devastating for voting rights,” said Lakin, who is involved in the case.

The Trump administration has already suggested support for that type of legal argument in a letter it sent to Texas officials suggesting that the current map is unconstitutional because it was drawn along racial lines, partly to comply with the Voting Rights Act.

Meanwhile, the current map in Texas is still being challenged in court by civil rights groups that allege it violates the Voting Rights Act.

Amid the trend toward partisan line-drawing, some states have undertaken efforts to de-politicize the process by setting up commissions instead of allowing lawmakers to do the job. There are 18 commissions of some type, although only eight of them are truly independent.

The Supreme Court narrowly upheld the use of independent commissions in a 2015 ruling. The court’s composition has changed since then, meaning it is unclear whether it would reach the same conclusion now.

Meanwhile, as California Democrats scramble to try to override their redistricting commission in response to the Texas plan, it may make less political sense for states to set commissions up in future.

“It dramatically undermines the incentives to create commissions,” Pildes said.

At the time of the partisan gerrymandering ruling, liberal Justice Elena Kagan warned of the consequences of the Supreme Court’s deciding not to step in over gerrymandered maps in North Carolina and Maryland.

“The practices challenged in these cases imperil our system of government,” she wrote. “Part of the Court’s role in that system is to defend its foundations. None is more important than free and fair elections.”