Share this @internewscast.com

MONTGOMERY, Ala. – On March 7, 1965, Charles Mauldin stood bravely near the forefront of the march for voting rights as they encountered countless state troopers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama.

The violence that awaited them shocked the nation and galvanized support for the passage of the U.S. Voting Rights Act a few months later.

This Wednesday marks 60 years since the historic legislation became law. Those who were central to the struggle for Black Americans’ voting rights shared their memories of the battle and voiced concerns about the possible backsliding of these hard-earned rights.

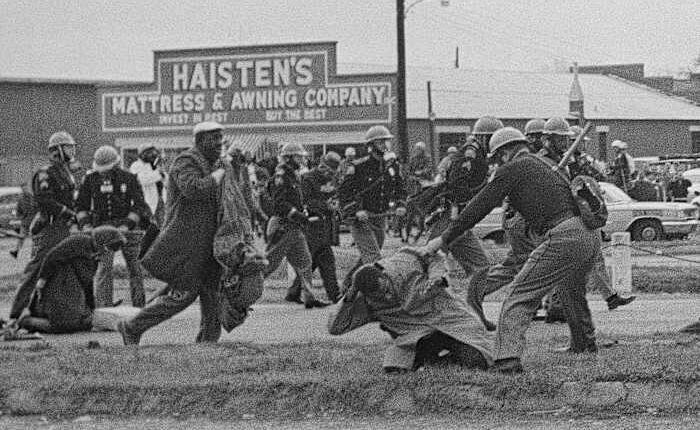

Bloody Sunday in Alabama, 1965

Mauldin, merely 17 at the time, took part in the doomed “Bloody Sunday” march. Notably, John Lewis, who later served as a prominent congressman for Georgia, and Hosea Williams led the marchers, with Mauldin following closely behind as a member of the third pair.

“By then, we had moved beyond fear. The injustice in Selma against us was so blatant that we were resolved to confront it no matter the cost,” reflected Mauldin, now 77 years old.

As recounted by Mauldin, the leader of the state troopers informed them that they were unlawfully assembled and gave them two minutes to clear out. Williams requested a moment to pray.

At once, the state troopers, equipped with gas masks, helmets, along with deputies and mounted men, launched an assault on the marchers — attacking men, women, and children indiscriminately. They wielded billy clubs, unleashed tear gas, and charged with their horses and cattle prods.

A cause worth dying for

Richard Smiley, then 16, was also among the marchers. He stashed candy in his pockets so he would have something to eat in case they went to jail.

As they approached the bridge, he saw about 100 white men on horseback.

“The only qualification they needed was to hate Blacks,” Smiley said.

“Our knees were knocking. We didn’t know whether we were going to get killed. We were afraid but we weren’t going to let fear stop us,” Smiley, 76, recalled. “At that point we would’ve gave up our life for the right to vote. That’s just how important it was.”

Selma in 1965 was a “very poor city and a racist city,” he said. He said there were some “white people in the town that supported our cause, but they couldn’t stand up” because of what would happen to them.

Echoes of the past

The Voting Rights Act led to sweeping change across the American South as discriminatory voting practices were dismantled and Black voter turnout surged. Democratic President Lyndon Johnson called the act “a triumph for freedom as huge as any victory won on any battlefield,” when he signed it on Aug. 6, 1965.

However, both Mauldin and Smiley see echoes of the past in the current political climate. While not as extreme as the policies of the Jim Crow South, Mauldin said there are attacks on the rights of Black and brown voters.

“The same struggle we had 61 years ago is the same struggle we had today,” Mauldin said.

Some states have enacted laws that make it harder not easier to vote, with voter ID requirements, limits to mail voting and other changes. President Donald Trump and Republican-led states have pushed sweeping rollbacks of diversity, equity and inclusion initiatives with Trump declaring he “ended the tyranny” of such programs.

The Justice Department, once focused on protecting access to voting, is taking steps to investigate alleged voter fraud and noncitizen voting. The department is joining Alabama in opposing a request to require the state to get future congressional maps precleared for use, calling it “a dramatic intrusion on principles of federalism.”

A long, unfinished struggle

The fight for voting rights was a long struggle, as is the struggle to maintain those rights, said Hank Sanders, a former state senator who helped organize the annual Bloody Sunday commemoration in Selma.

Two weeks after Bloody Sunday, the Rev. Martin Luther King led marchers out on the walk to Montgomery, Alabama, to continue the fight for voting rights. Sanders was among the thousands who completed the last legs of the march and listened as King’s famous words “How long, not long” thundered down over the crowd.

“That was a very powerful moment because I left there convinced that it wouldn’t be long before people would have the full voting rights,” Sanders, 82, recalled. He said the reality it would be a longer fight set in the next year when a slate of Black candidates lost in an overwhelmingly Black county

The Voting Rights Act for decades required that states with a history of discrimination — including many in the South — get federal approval before changing the way they hold elections. The requirement of preclearance effectively went away in 2013 when the U.S. Supreme Court ruled, in a case arising from Alabama, that the provision determining which states are covered was outdated and unconstitutional.

That led to a flood of legislation in states impacting voting, Sanders said. “It’s no longer a shower, t’s a storm,” Sanders said.

“I never thought that 50 years later, we’d still be fighting,” Sanders said, “not just to expand voting right but to be able to maintain some of the rights that we had already obtained.”

Copyright 2025 The Associated Press. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, broadcast, rewritten or redistributed without permission.